Characteristics of particular forest producers in Mexico

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v13i5.3228Keywords:

family properties, forest property, small property, timber exploitationAbstract

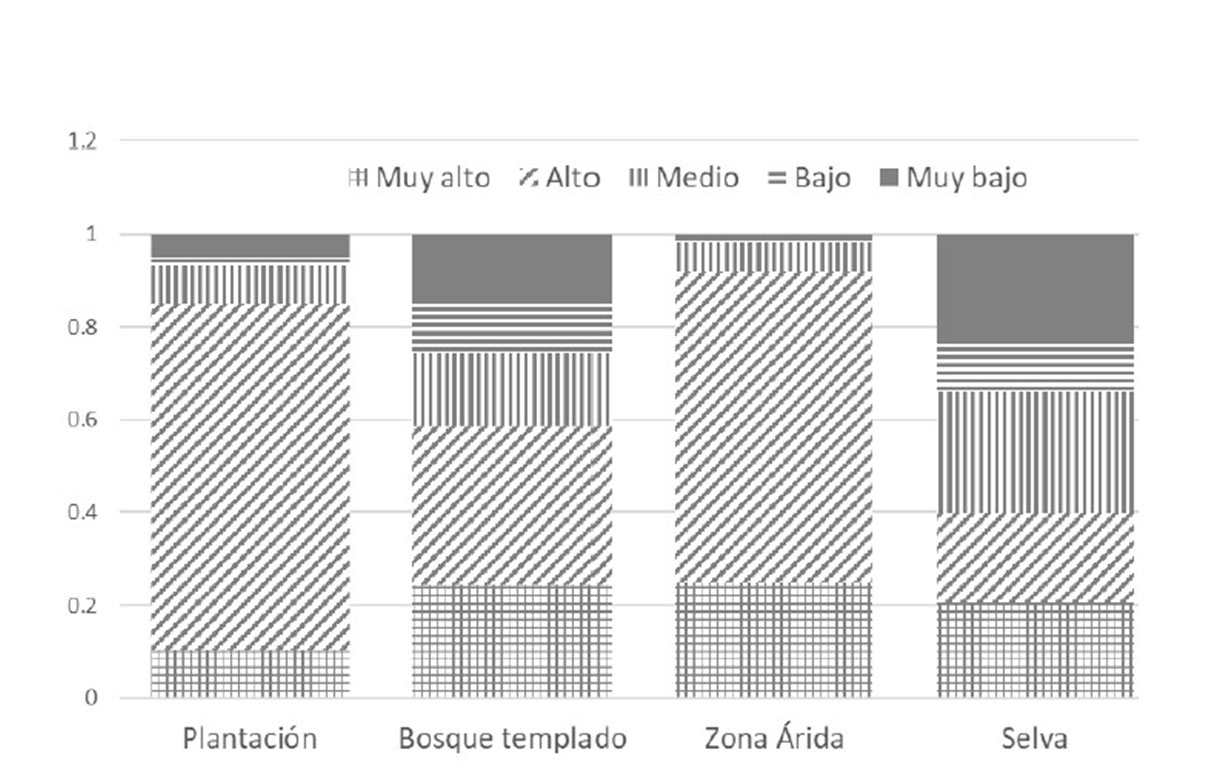

Globally, 74% of forest area is owned by governments. In Mexico, private property can be collective (colony, ejidos and communities) or individual (natural or juridical persons). Individual forest property is related to the concept of small property, defined by the Agrarian Law as an area of land owned by a single owner. The objective was to characterize privately owned forest properties (POFPs) in terms of their abundance, composition and uses, as well as the general characteristics of the type of forest management applied, based on the fusion of available data and some assumptions. The cover of series VI of INEGI was used to characterize the vegetation cover of individual properties. Land use change estimates were made by difference between the cover of series VI and series III. Timber and non-timber harvest volumes and areas are derived from the relational database developed in Microsoft Access®. The results show that there are about 769 000 ha in POFPs under timber exploitation of a potential of 9.4 Mha of primary and secondary vegetation forests located on private properties; forests that could be added to sustainable forest management. It was observed that only 8% of temperate forests on private properties are legally exploited, so there is a large area of temperate forests that could be incorporated into sustainable forest management. POFPs have an important participation in timber production, representing an important component in forest management at the national level.

Downloads

References

Agrawal, A. 2007. Forests, governance, and sustainability: common property theory and its contributions. Inter. J. Commons. 1(1):111-136. Ask, P. and Carlsson, M. 2000. Nature conservation and timber production in areas with fragmented ownership patterns. Forest Pol. Econ. 1(3-4):209-223. Bray, D. B. 2020. Mexico’s community forest Enterprises: success on the commons and the seeds of a Good Anthropocene. University of Arizona Press. 292 p. Canadas, M. J.; Novais, A. and Marques, M. 2016. Wildfires, forest management and landowner’s collective action: A comparative approach at the local level. Land Use Policy. 56:179-188.

Carrillo-Anzures, F.; Acosta-Mireles, M.; Flores-Ayala, E.; Torres-Rojo, J. M.; Sangerman-Jarquín, D. M.; González-Molina, L. y Buendía-Rodríguez, E. 2017. Caracterización de productores forestales en 12 estados de la República Mexicana. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 8(7):1561-1573. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i7.512

CONANP. 2019. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Áreas naturales protegidas decretadas. http://sig.conanp.gob.mx/website/pagsig/datos-anp.htm#:~:text=%C3%81reas %20Naturales%20Protegidas%20decretadas,una%20superficie%20de%20596%2C867.34%20hect%C3%A1reas.

CONAFOR. 2019. Comisión Nacional Forestal. El sector forestal mexicano en cifras 2019. CONAFOR. Zapopan, México. http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/ 1/7749El%20Sector%20Forestal%20Mexicano%20en%20Cifras%202019.pdf. CONABIO. 2021. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Geoportal de áreas las naturales protegidas. https://monitoreo.conabio.gob.mx/areas-protegidas.html.

CONAPO. Consejo Nacional de Población. 2016. Índices de marginación municipal 1990-2015. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/datos-abiertos-del-indice-de-marginacion.

Conway, M. C.; Amacher, G. S.; Sullivan, J. and Wear, D. 2003. Decisions nonindustrial forest landowners make: an empirical examination. J. Forest Econ. 9(3):181-203. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1078/1104-6899-00034

Cubbage, F. W.; Davis, R. R.; Rodríguez, P. D.; Mollenhauer, R.; Kraus-Elsin, Y.; Frey, G. E.; González-Hernández, I. A.; Albarrán-Hurtado, H.; Salazar-Cruz, A. and Chemor-Salas, D. N. 2015. Community forestry enterprises in Mexico: sustainability and competitiveness. J. Sustain. For. 34(6-7):623-650. DOF. 2018. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. (Ed.). Vespertina decreto por el que se abroga la Ley General de Desarrollo Forestal Sustentable, publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2-48 pp. Fischer, A. P.; Bliss, J.; Ingemarson, F.; Lidestav, G. and Lönnstedt, L. 2010. From the small woodland problem to ecosocial systems: the evolution of social research on small-scale forestry in Sweden and the USA. Scandinavian J. For. Res. 25(4):390-398. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2015.1040514

Gibson, C. C.; Lehoucq, F. E. and Williams, J. T. 2002. Does privatization protect natural resources? Property rights and forests in Guatemala. Soc. Sci. Q. 83(1):206-225. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6237.00079

Hardin, G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 162(3859):1243-1248. Honey-Rosés, J. 2009. Illegal logging in common property forests. Soc. Nat. Resour. 22(10):916-930. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

INEGI. 2016. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Actualización del marco censal agropecuario 2016. http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/programas/amca/2016/.

INEGI. 2017. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Cobertura de uso del suelo y vegetación serie VI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/usosuelo/#descargas.

Larson, A. M.; Barry, D.; Dahal, G. R. and Colfer, C. J. P. 2010. Forests for people: community rights and forest tenure reform. Earthscan, Londres. 263 p. Mendoza, M. A.; Fajardo, J. J.; Curiel, G.; Domínguez, F.; Apodaca, M.; Rodríguez-Camarillo, M. G. and Zepeta, J. 2015. Harvest regulation for multi-resource management, old and new approaches (old and new). Forests. 6(3):670-691. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/f6030670

Molnar, A.; Barney, K.; DeVito, M.; Karsenty, A.; Elson, D.; Benavides, M.; Tipula, P.; Soria, C.; Shearman, P. and France, M. 2011. Land acquisition of rights on forest lands for tropical timber concessions and commercial wood plantations. Washington, DC. USA. The International Land Coalition. 6 p.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press. 3-8 pp. Pérez-Verdín, G.; Cassian-Santos, J. M.; Von Gadow, K. and Monarrez-Gonzalez, J. C. 2015. Molinillos private forest estate, Durango, Mexico. In: forest plans of North America Academic Press. 97-105 pp. Pukkala, T. 2016. Which type of forest management provides most ecosystem services? For. Ecosyst. 3(1):1-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-799936-4.00013-8

RAN. 2012. Registro Agrario Nacional. Padrón e historial de núcleos agrarios: PHINA, V3. <http://phina.ran.gob.mx:8080/phina2/>.

Sunderlin, W.D.; Hatcher, J. and Liddle, M. 2008. From exclusion to ownership? Challenges and opportunities in advancing forest tenure reform. Rights and Resource Initiative. Washington, DC. 54 p. Toledo-Aceves, T.; Gerez-Fernández, P. y Porter-Bolland, L. 2019. ¿Qué se necesita para avanzar hacia el manejo de los bosques de niebla secundarios en México? CCMSS, México. 1 p. http://www.ccmss.org.mx/. Torres, T. F. y Rojas, M. A. 2018. El suelo agrícola en México: retrospección y prospectiva para la seguridad alimentaria. Realidad, datos y espacio. Rev. Inter. Est. Geogr. 9(3):137-155.

Torres-Rojo, J. M. y Amador-Callejas, J. 2015. Características de los núcleos agrarios forestales en México. In: desarrollo forestal comunitario: la política pública. Torres-Rojo, J. M. (Ed.). CIDE. Coyontura y Ensayo. 15-38 pp.

Tucker, C. M. 1999. Private versus common property forests: forest conditions and tenure in a Honduran community. Human Ecol. 27(2):201-230. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018721826964

White A. and Martin, A. 2002. Who owns the world’s forests? Forest tenure and public forests in transition. Forest Trends. Wasington, DC. 30 p. Zinda, J. A. and Zhang, Z. 2018. Stabilizing forests and communities: accommodative buffering within China’s collective forest tenure reform. The China Quarterly. 235:828-848.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.