Evaluation of selected papaya lines for the preservation of desirable traits

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v15i5.3723Keywords:

Carica papaya, hermaphrodite, ‘maradol’ genotype, plant sexingAbstract

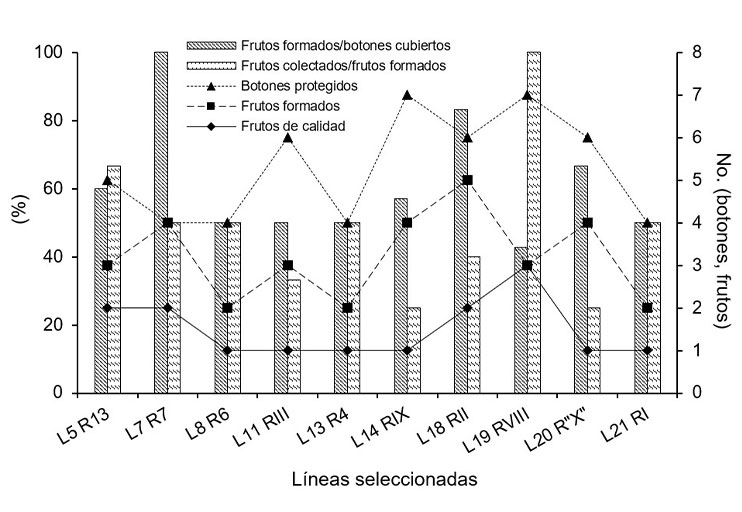

There are currently few varieties of papaya in Mexico and the dominant one is ‘Maradol’, which over time has been vulnerable. Nonetheless, developing varieties for seed production is challenging. The objective was to evaluate outstanding and adapted papaya lines for the conservation of desirable traits. In the field, 23 lines of the ‘Maradol’ type were evaluated in Antúnez Michoacán, Mexico, in 2022. Initially, plant height, stem circumference, number of leaves and height to first fruit were recorded. During plant development, outstanding plants were identified and their pollination was controlled. In developed fruits, polar and equatorial circumference, weight, width and firmness of the pulp, and soluble solids were recorded. The development of plants presented differences, whose variability between lines allowed the identification of morphological characteristics of interest. Only 10 lines had this condition. In pollination control, the number of fruits formed over the flower buds decreased and the fruits collected over the fruits formed decreased. The characterization of fruits, except for soluble solids, showed differences. Multivariate analysis indicated variability associated with each principal component. It is concluded that of 23 papaya lines, only 43.48% presented outstanding plants. Within the lines, between 5 and 10% of the plants were selected. In the pollination control, they tended to decreased among the stages since only 28% of fruits were obtained. The selected lines showed fruit variability.

Downloads

References

Aikpokpodion, P. O. 2012. Assessment of genetic diversity in horticultural and morphological traits among papaya (Carica papaya) accessions in Nigeria. Fruits. 67(3):173-187. https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits/2012011.

Álvarez, H. J. C. y Tapia, V. L. M. 2019. Selección de plantas de papaya sobresalientes en ambientes comerciales con fines de mejoramiento. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 23(esp):303-311. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i23.2029.

Bhattacharya, J. and Khuspe, S. S. 2001. In vitro and in vivo germination of papaya (Carica papaya L.) seed. Scientia Horticulturae. 91(1-2):39-49.

Barbosa, C. D.; Viana, A. P.; Quital, S. S. R. and Pereira, M. G. 2011. Artificial neural network analysis of genetic diversity in Carica papaya L. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 11(3):224-231. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-70332011000300004.

Coria, A. V. M.; Álvarez, H. J. C.; Venegas, G. E. y Vidales F. I. 2017. Agenda técnica agrícola Michoacán. SAGARPA. COFUPRO. INIFAP. 270 p.

Damasceno, J. P. C.; Santana, P. T. N. and Gonzaga, P. M. 2018. Estimation of genetic parameters of flower anomalies in papaya. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 18(1):9-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1984-70332018v18n1a2.

FAOSTAT. 2021. Estadísticas de la producción mundial de papaya. https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL.

Hammer, Ø. 2018. PAST V. 3.2 Reference manual. Natural history museum, university of Oslo. 262 p.

Honoré, M. N.; Belmonte-Ureña, L. J.; Navarro-Velazco, A. and Camacho-Ferre, F. 2020. Effects of the size of papaya (Carica papaya L.) seedling with early determination of sex on the yield and the quality in a greenhouse cultivation in continental Europe. Scientia Horticulturae. 265(109218):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109218.

Karunamoorthi, K.; Kim, H. M.; Kaliyaperumal, J.; Jerome, X. and Jayarama, V. 2014. Papaya: a gifted nutraceutical plant a critical review of recent human health research. Tang Humanitas Medicine. 4(1):1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.5667/tang.2013.0028.

Marin, S. L. D.; Pereira, M. G.; Amaral, A. T.; Martelleto, L. A. P. and Ide, C. D. 2006. Heterosis in papaya hybrids from partial diallel of ‘Solo’ and ‘Formosa’ parents. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 6(1):24-29. Doi: 10.12702/1984-7033.v06n01a04.

Nascimento, A. L.; Schmildt, O.; Ferreguetti, G. A.; Krause, W.; Alexandre, R. S.; Schmildt, E. R.; Cavatte, P. C. and Amarral, A. T. 2019. Inheritance of leaf color in papaya. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 19(2):161-168.

Nunes, L. L.; Santa-Catarina, R.; Brito, B. G.; Ribeiro, B. F.; Fiorio, V. J. C. and Gonzaga P. M. 2018. Adaptability and stability of papaya hybrids affected by production seasonality. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 18(4):357-364.

Oliveira, E. J.; Pereira, D. N. L. and Loyola, D. J. L. 2012. Selection of morpho agronomic descriptor for characterization of papaya cultivars. Euphytica. 185(2):253-265.

Ram, M. 2005. Papaya. Indian council of agricultural research, New Delhi. 1st. Ed. India. 189 p.

Santana, C. A. F.; Medeiros, A. E. F.; Schmildt, E. R.; Nogueira, C. A. y Schmildt, O. 2019. Advances observed in papaya tree propagation. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. 41(5):1-15. http://dx.doi.org /10.1590/0100-29452019036.

Saran, P. L.; Choudhary, R.; Solanki, I. S.; Patil, P. and Kumar, S. 2015. Genetic variability and relationship studies in new Indian papaya (Carica papaya L.) germplasm using mofphological and molecular markers. Turkish journal of agriculture and forestry. 39(2):310-321. Doi: 10.3906/tar-1409-148.

SAS Institute Inc. 2002. The SAS System for Windows 9.0. Cary, NC, USA. 421 p.

SIAP-SADER. 2023. Estadísticas de la producción nacional de papaya. https://nube.siap.gob.mx/avance-agricola/.

SIAP. 2017. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Atlas agroalimentario. 1ra. Ed. Ciudad de México. 231 p.

Silva, C. A.; Nascimiento, A. L.; Pereira, F. J.; Schmildt, O.; Garcia, M. R.; Sobreira, A. R.; Ferregueti, G. A. and Romais, S. E. 2017. Genetic diversity among papaya accessions. African journal of agricultural. 12(23):2041-2048.

SNICS-SAGARPA. 2014. Regla para la calificación de semilla de papaya (Carica papaya L.). 23 p.

SNITT-SAGARPA. 2016. Agenda nacional de investigación, innovación y transferencia de tecnología agrícola 2016-2022. 1ra. Ed. México. 197 p.

Urasaki, N.; Tarora, K.; Shudo, A.; Ueno, H.; Tamaki, M.; Miyagi, N.; Adaniya, S. and Matsumura, H. 2012. Digital transcriptome analysis of putative sex determination genes in papaya (Carica papaya). 7(7):1-9. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040904.

Vivas, M.; Silveira, S. F.; Silva, V. J. M.; Dias, S. P. H.; Carvalho, M. B.; Daher, R. F.; Amaral, J. A. T. and Gonzaga, P. M. 2017. Phenotypic characterization of papaya genotypes to determine powdery mildew resistance. Crop breeding and applied biotechnology. 17(3):198-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1984-70332017v17n3a31.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.