Grain production potential of soybean cultivation in the Puebla Valley

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v13i5.3229Keywords:

early varieties, grain production, high plateauAbstract

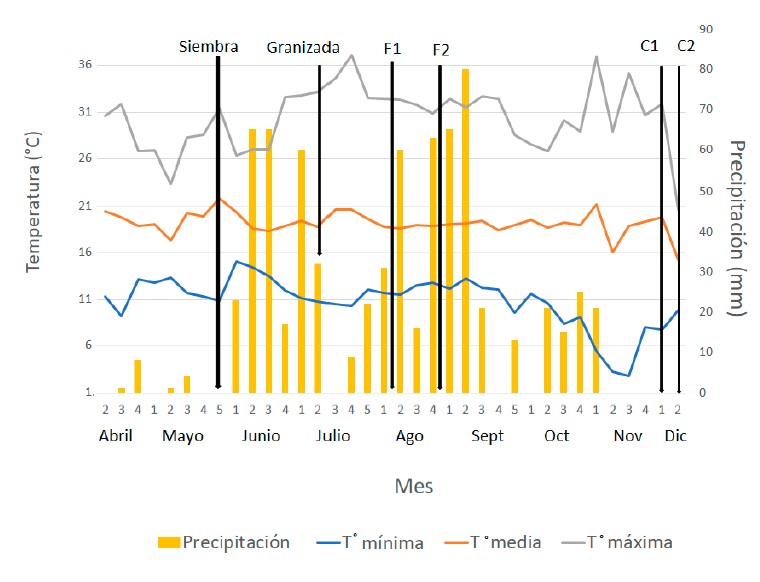

In Mexico, soybean production does not meet demand, so it is imported from other countries. This crop, produced mainly in the tropics, can be extended to the temperate zone to increase domestic production. Therefore, the present study evaluated the productive behavior of seven experimental selections and two commercial varieties of soybean in 2018, in three sites of the Puebla Valley with altitudes ranging from 2 190 to 2 240 m. The experimental design was in random blocks with four repetitions analyzed in a combined way. The experimental unit was four furrows five meters long and 70 cm wide. The variables evaluated were flowering, plant height, canopy width and grain production. The earliest varieties to flowering were ‘Hoja Seca Original’, ‘Hoja Seca Vainas Abundantes’ and ‘Varita’ with 81, 78 and 82 days, respectively, compared to the others that had 99 days on average. The locality where flowering occurred the fastest was Coronango (89 days). The varieties that differed the most in yield were Varita and Nainary, which on average had 3.42 and 2.02 t ha-1. The locality of La Ciénega had a higher yield (3.77 t ha-1) than the other two localities. In conclusion, the early varieties Varita, Hoja Seca Vainas Abundantes and Hoja Seca Original were the earliest and had the highest grain yield, therefore, they may be the most recommended for the area in question, which shows some potential.

Downloads

References

Abrahão, G. M. and Costa, M. H. 2018. Evolution of rain and photoperiod limitations on the soybean growing season in Brazil: the rise (and possible fall) of double-cropping systems. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 256-257:32-45. Cortez, M. E.; Pérez, M. J.; Rodríguez, C. F. G.; Martínez, C. J. L. y Cervantes, C. L. 2013. Rendimiento y respuesta de variedades de soya a mosca blanca Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) en tres fechas de siembra. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 4(7):1067-1080. Cochran, W. G. and Cox, G. M. 1992. Experimental designs. Second (Ed.). Wiley. New York. 391-413 pp. Gavioli, E. A. 2013. Explanations for the rise of soybean in Brazil. In: a comprehensive survey of international soybean research- genetics, physiology, agronomy and nitrogen relationships. J. E. Board (Ed). IntechOpen.1-25 pp. https://doi.org/10.5772/51678. Gómez, M. R.; Gómez, M. R.; Morales, D. P.; Martínez, C. E. y Zarazúa, D. M. A. 2014. Tecnología para la producción de soya en el estado de Hidalgo. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Centro de Investigaciones Regional Centro (CIRCE)-Sitio Experimental Hidalgo. Pachuca, Hidalgo. Folleto técnico núm. 1. 48 p. INAFED. 2017. Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. http://www.inafed.gob.mx/work/enciclopedia/EMM21puebla/municipios/21034a.html.

Janas, K. M.; Cvikrová, M.; Pałągiewicz, A. and Eder, J. 2000. Alterations in phenylpropanoid content in soybean roots during low temperature acclimation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38(7-8):587-593. López, S. H. y Muñoz, O. A. 1989. Ensayo de variedades de soya (Glycine max L. Merr.) bajo condiciones de temporal crítico en la Mixteca Poblana. Rev. Chapingo. 60-61(1):59-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0981-9428(00)00778-6

Masino, A.; Rugeroni, P.; Borrás, L. and Rotundo, J. L. 2018. Spatial and temporal plant-to-plant variability effects on soybean yield. Eur. J. Agron. 98:14-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2018.02.006

Nicoa, M.; Miralles, D. J. and Kantolic, A. G. 2015. Post-flowering photoperiod and radiation interaction in soybean yield determination: direct and indirect photoperiodic effects. Field Crops Res. 176:45-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2015.02.018

Ohnishi, S.; Miyoshi, T. and Shirai, S. 2010. Low temperature stress at different flower developmental stages affects pollen development, pollination, and pod set in soybean. Environ. Exp. Bot. 69(1):56-62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.02.007

OECD. 2000. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Consensus document on the biology of Glycine max (L.) Merr. (Soybean). Series on harmonization of regulatory oversight in biotechnology. 15:11-14.

Pagano, M. C. and Miransari, M. 2016. The importance of soybean production worldwide. In: abiotic and biotic stresses in soybean production: soybean production volume one. First (Ed), London UK. Academic Press, Elsevier Inc. 1-26. pp. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801536-0.00001-3

Piper, E. L.; Smit, M. A.; Boote, K. J. and Jones, J. W. 1996. The role of daily minimum temperature in modulating the development rate to flowering in soybean. Field Crops Res. 47(2-3):211-220. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4290(96)00015-9

Sanghera, G. S.; Wani, S. H.; Hussain, W. and Singh, N. B. 2011. Engineering cold stress tolerance in crop plants. Current Genomics. 12(1):30-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2174/138920211794520178

SIAP-SIACON. 2018. Principales estados productores de soya en México. http://infosiap.siap.gob.mx:8080/agricola-siap-gobmx/AvanceNacionalSinPrograma.do.

Simorte, T.; Flores, F.; Torres, A. and Moreno, M. T. 1995. Estudio de los componentes del rendimiento en generaciones segregantes. Investigación agraria, producción y protección vegetales. 10(3):402-413.

Tambussi, E. A.; Bartoli, C. G.; Guiamet, J. J.; Beltrano, J. and Araus, J. L. 2004. Oxidative stress and photodamage at low temperatures in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) leaves. Plant Sci. 167(1):19-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.02.018

USDA. 2019. Mexico: production, supply and distribution (PSD) for soybeans. https://www.usda.gov.

Vanhiea, M.; Deena, W.; Lauzonb, D. L. and Hookerc, D. C. 2015. Effect of increasing levels of maize (Zea mays L.) residue on no-till soybean (Glycine max Merr.) in northern production regions. Soil Tillage Res. 150:201-210. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.01.011

Yepes, A. y Silveira, B. M. Respuestas de las plantas ante los factores ambientales del cambio climático global (Revisión). Colombia Forestal. 14(2):213-232. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.colomb.for.2011.2.a06

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.