Impactos del cambio climático en la producción de maíz en México

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v15i1.3327Palabras clave:

Zea mays L., eventos extremos, mitigación y adaptación, seguridad alimentaria, vulnerabilidadResumen

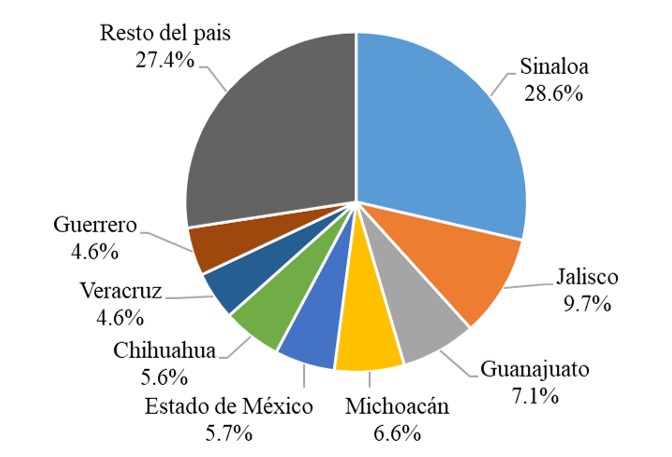

Las actividades antropogénicas han sumado lo suficiente para ocasionar alteraciones importantes en el clima a nivel global, en los últimos 20 años se ha pronunciado un fenómeno de características extremas denominado ‘cambio climático’, el cual ha sido encargado de causar una variabilidad climática, cuyo nivel de afectación se extiende en todas las escalas geográficas. Esta investigación se realizó en al año 2022, teniendo como objetivo conocer los impactos del cambio climático en el sistema productivo del cultivo de maíz en México, dada su gran relevancia nutricional, cultural y económica. Se describe la variabilidad climática y los eventos extremos que ocurren en México y que de alguna manera tienen una relación directa con la producción del maíz, como la precipitación, temperatura, heladas, granizadas, sequías e inundaciones. A nivel mundial, México destaca en los primeros lugares en producción y consumo de maíz, la población actual supera los 126 millones de personas y resulta una condición que manifiesta una gran demanda, teniendo que realizar una fuerte exportación del grano año con año, poniendo en manifiesto la insostenibilidad de la seguridad alimentaria del país. Esta situación se agrava cuando el cambio climático y la variabilidad climática, afectan directamente en los requerimientos de mayor importancia para el establecimiento de un cultivo y que afectan directamente con todas las etapas de crecimiento y desarrollo, presentando una disminución del rendimiento actual y futuro.

Descargas

Citas

Abbass, K.; Qasim, M. Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H. and Younis, I. 2022. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(28):42539-42559. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-022-19718-6.

Adeagbo, O. A.; Ojo, T. O. and Adetoro, A. A. 2021. Understanding the determinants of climate change adaptation strategies among smallholder maize farmers in South-west, Nigeria. Heliyon. 7(2):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06231.

Arce-Romero, A. R.; Monterroso-Rivas, A. I.; Gómez-Díaz, J. D. and Palacios-Mendoza, M. A. 2018. Potential yields of maize and barley with climate change scenarios and adaptive actions in two sites in Mexico. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 687(1):197-208. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70187-5-15.

Baum, M. E.; Licht, M. A.; Huber, I. and Archontoulis, S. V. 2020. Impacts of climate change on the optimum planting date of different maize cultivars in the central US Corn Belt. Eur. J. Agron. 119(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2020.126101.

Bedeke, S.; Vanhove, W.; Gezahegn, M.; Natarajan, K. and Van Damme, P. 2019. Adoption of climate change adaptation strategies by maize-dependent smallholders in Ethiopia. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci. 88(1):96-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2018.09.001.

Çakir, R. 2004. Effect of water stress at different development stages on vegetative and reproductive growth of corn. Field Crops Res. 89(1):1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.fcr.2004.01.005.

CENAPRED. 2014. Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres. Características del impacto socioeconómico de los principales desastres ocurridos en México. México, DF.

CENAPRED. 2020. Centro Nacional de Prevención de Desastres. Características del impacto socioeconómico de los principales desastres ocurridos en México. México, DF.

CONAGUA. 2022. Resúmenes mensuales de temperaturas y lluvia. https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/temperaturas-y-lluvias/resumenes-mensuales-de-temperaturas-y-lluvias.

CONAPO. 2019. Consejo Nacional de Población. Secretaría de Gobernación. Colección. Proyecciones de la población de México y las entidades federativas 2016-2050 República Mexicana. Ciudad de México, México.

Cuervo-Robayo, A. P.; Ureta, C.; Gómez-Albores, M. A.; Meneses-Mosquera, A. K.; Téllez-Valdés, O. and Martínez-Meyer, E. 2020. One hundred years of climate change in Mexico. PLoS ONE. 15(7):1-19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0209808.

FAO. 2017. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The future of food and agriculture-Trends and challenges. Rome, Italy. ISBN: 978-92-5-109551-5. https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf.

FAO. 2023. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT-Agriculture Database. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL. 22/09/2023.

Frieler, K.; Schauberger, B.; Arneth, A.; Balkovic, J.; Chryssanthacopoulos, J.; Deryng, D.; Elliott, J.; Folberth, C.; Khabarov, N.; Müller, C.; Olin, S.; Pugh, A. M. T.; Schaphoff, S.; Schewe, J.; Schmid, E.; Warszawski, L. and Levermann, A. 2017. Understanding the weather signal in national crop-yield variability. Earth’s future. 5(6):605-616. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EF000525.

Giller, K. E.; Delaune, T. and Silva, J. V. 2021. The future of farming: Who will produce our food? Food Sec. 13(5):1073-1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01184-6.

González-Celada, G.; Ríos, N.; Benegas-Negri, L. and Argotty-Benavides, F. 2021. Impact of the climate change and the land use/land cover change in the hydrological and water erosion response in the Qui scab river subbasin. Tecnología y Ciencias del Agua. 12(6):328-362. https://doi.org/10.24850/J-TYCA-2021-06-08.

Harkness, C.; Semenov, M. A.; Areal, F.; Senapati, N.; Trnka, M.; Balek, J. and Bishop, J. 2020. Adverse weather conditions for UK wheat production under climate change. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 282-283(1):1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.107862.

INEGI. 2020. Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/.

IPCC. 2019. Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. Calentamiento global de 1.5 °C. https://www.riob.org/es/documentos/ calentamiento-global-de-15-degc.

IPCC. 2021. Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. In: contribution of working group i to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Ed. Masson-Delmotte, V. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.

IPCC. 2022. Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. WGI Interactive Atlas: Regional information. de Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sitio web: https://interactive-atlas.ipcc.ch/regionalinformation#ey J0eXBlIjoiQVRMQVMiLCJjb21tb25zIjp7ImxhdCI6OTc3MiwibG5nIjo0MDA2OTIsInpv.

Kang, Y.; Ma, X. and Khan, S. 2013. Predicting climate change impacts on maize crop productivity and water use efficiency in the loess plateau. Irrigation and Drainage. 63(3):394-404. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.1799.

Leng, G. 2019. Uncertainty in assessing temperature impact on U.S. maize yield under global warming: the role of compounding precipitation effect. J. Geo. Res. Atmos. 124(12):6238–6246. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD029996.

Lizaso, J. I.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Rodríguez, L.; Gabaldon-Leal, C.; Oliveira, J. A.; Lorite, I. J.; Sánchez, D.; García, E. and Rodríguez, A. 2018. Impact of high temperatures in maize: phenology and yield components. Field Crops Res. 216(1):129-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2017.11.013.

Lobato-Sánchez, R. y Altamirano-Carmen, M. Á. 2017. Detección de la tendencia local del cambio de la temperatura en México. Tecnología y Ciencias del Agua. 8(6):101-116. https://doi.org/10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07.

Lv, Z.; Li, F. and Lu, G. 2020. Adjusting sowing date and cultivar shift improve maize adaption to climate change in China. Mitigation and adaptation strategies for global change. 25(1):87-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-019-09861-w.

Mastachi-Loza, C. A.; Becerril-Piña, R.; Gómez-Albores, M. A.; Díaz-Delgado, C.; Romero-Contreras, A. T.; Garcia-Aragon, J. A. and Vizcarra-Bordi, I. 2016. Regional analysis of climate variability at three-time scales and its effect on rainfed maize production in the upper lerma river basin, Mexico. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 225(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.03.041.

Mills, G.; Sharps, K.; Simpson, D.; Pleijel, H.; Frei, M.; Burkey, K.; Emberson, L.; Uddling, J.; Broberg, M.; Feng, Z.; Kobayashi, K. and Agrawal, M. 2018. Closing the global ozone yield gap: quantification and benefits for multitrees tolerance. Global Change Biology. 24(10):4869-4893. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14381.

Monterroso, A. and Conde, C. 2015. Exposure to climate and climate change in Mexico. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk. 6(4):272-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 19475705.2013.847867.

Murray-Tortarolo, G. N.; Jaramillo, V. J. and Larsen, J. 2018. Food security and climate change: the case of rainfed maize production in Mexico. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 253-254(1):124-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet. 2018.02.011.

Nandan, R.; Woo, D. K.; Kumar, P. and Adinarayana, J. 2021. Impact of irrigation scheduling methods on corn yield under climate change. Agricultural Water Management. 255(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106990.

Noein, B. and Soleymani, A. 2022. Corn (Zea mays L.) physiology and yield affected by plant growth regulators under drought stress. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 41(2):672–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10332-3.

Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L. and Mathenge, M. 2016. Effects of climate variability and change on agricultural production: the case of small-scale farmers in Kenya. NJAS Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences. 77:71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas. 2016.03.005

ONU. 2016. Organización de las Naciones Unidas. Agenda 2030 y los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. una oportunidad para américa latina y el caribe. Santiago, Chile. CEPAL. https://www.cedhnl.org.mx/bs/vih/secciones/planes-y-programas/ Agenda-2030-y-los-ODS.pdf. 9-13 pp.

Ortiz-Rosales, M. Á. y Ramírez-Abarca, O. 2017. Proveedores e industrias de destino de maíz en México. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo. 14(1):61-82. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci-arttextypid=S187054722017000 100061ylng=esytlng=es.

PINCC. 2022. Programa de Investigación en Cambio Climático. Fue el cuarto año más caluroso en México del que se tenga registro. Programa de investigación en cambio climático, Instituto de Ciencias de la Atmósfera y Cambio Climático-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). https://www.pincc.unam.mx/ 2021-fue-el-cuarto-ano-mas-caluroso-en-mexico-del-que-se-tenga-registro/.

Reyes, S. E.; Bautista M. F. y García, S. J. A. 2022. Análisis del mercado de maíz en México desde una perspectiva de precios. Acta Universitaria. 32(1):1-16. Doi. http://doi.org/10.15174.au.2022.3265.

Richardson, K. J.; Lewis, K. H.; Krishnamurthy, P. K.; Kent, C.; Wiltshire, A. J. and Hanlon, H. M. 2018. Food security outcomes under a changing climate: impacts of mitigation and adaptation on vulnerability to food insecurity. Climatic Change. 147(1-2):327-341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2137-y

Ruiz, C. J.; Medina, G. G.; González, E. D.; Ramírez, D. J.; Flores, L. H.; Ruiz, C. J.; Manríquez, O. J.; Zarazúa, V. P.; Díaz, P. G.; Ramírez, O. G. y Mora, O. C. 2011. Cambio climático y sus implicaciones en cinco zonas productoras de maíz en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2(1):309-323. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=263121431011.

Ruiz-Corral, J. A.; Ramírez-Díaz, J. L.; Hernández-Casillas, J. M.; Aragón-Cuevas, F.; Sánchez-Gonzáles, J. de J.; Ortega-Corona, A.; Medina-García, G. y Ramírez-Ojeda, G. 2011. Razas mexicanas de maíz como fuente de germoplasma para la adaptación al cambio climático. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2(1):365-379.

Santos, R. M. and Bakhshoodeh, R. 2021. Climate change global warming climate emergency versus general climate research: comparative bibliometric trends of publications. Heliyon. 7(11):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08219.

SIAP. 2020. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Avance de siembras y cosechas resumen por estado. http://infosiap.siap.gob.mx:8080/agricola-siap-gobmx/resumenproducto.do.

Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I. P.; Lešić, V. and Lemić, D. 2021. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects. 12(5):1-25. doi:10.3390/insects12050440.

Ureta, C.; González, E. J.; Espinosa, A.; Trueba, A.; Piñeyro-Nelson, A. and Álvarez-Buylla, E. R. 2020. Maize yield in Mexico under climate change. Agricultural Systems. 177(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102697.

Villalobos-González, A.; López-Castañeda, C.; Miranda-Colín, S.; Aguilar-Rincón, V. H.; y López-Hernández, M. B. 2017. Relaciones hídricas en maíces de Valles Altos de la Mesa Central de México en condiciones de sequía y fertilización nitrogenada. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 7(7):1651-1665. https://doi.org/10.29312/ remexca.v7i7.157.

Wang, Y.; Wang, C. and Zhang, Q. 2021. Synergistic effects of climatic factors and drought on maize yield in the east of northwest China against the background of climate change. Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 143(3-4):1017-1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-020-03457-0.

Welikhe, P.; Essamuah-Quansah, J.; Boote, K.; Asseng, S. and El Afandi, G. 2016. Impact of climate change on corn yields in alabama. Professional Agricultural Workers J. 4(1):1-14.

Wilson, A. B.; Avila-Diaz, A.; Oliveira, L.; Zuluga, C. F. and Mark, B. 2022. Climate extremes and their impacts on agriculture across the eastern corn belt region of the U.S. Weather and climate extremes. 37(1):1-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace. 2022.100467.

Ye, Q.; Lin, X.; Adee, E.; Min, D.; Assefa, M. Y.; Brien, D. and Ciampitti, I. A. 2017. Evaluation of climatic variables as yield-limiting factors for maize in Kansas. Inter. J. Climatol. 37(1):464-475. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5015.

Zúñiga, E. and Magaña, V. 2018. Vulnerability and risk to intense rainfall in Mexico. the effect of land use cover change. Investigaciones Geográficas. 95(1):1-18. https://doi.org/10.14350/rig.59465.

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2024 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0.

Los autores(as) que publiquen en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas aceptan las siguientes condiciones:

De acuerdo con la legislación de derechos de autor, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas reconoce y respeta el derecho moral de los autores(as), así como la titularidad del derecho patrimonial, el cual será cedido a la revista para su difusión en acceso abierto.

Los autores(as) deben de pagar una cuota por recepción de artículos antes de pasar por dictamen editorial. En caso de que la colaboración sea aceptada, el autor debe de parar la traducción de su texto al inglés.

Todos los textos publicados por Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas -sin excepción- se distribuyen amparados bajo la licencia Creative Commons 4.0 atribución-no comercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 internacional), que permite a terceros utilizar lo publicado siempre que mencionen la autoría del trabajo y a la primera publicación en esta revista.

Los autores/as pueden realizar otros acuerdos contractuales independientes y adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión del artículo publicado en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (por ejemplo incluirlo en un repositorio institucional o darlo a conocer en otros medios en papel o electrónicos) siempre que indique clara y explícitamente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

Para todo lo anterior, los autores(as) deben remitir el formato de carta-cesión de la propiedad de los derechos de la primera publicación debidamente requisitado y firmado por los autores(as). Este formato debe ser remitido en archivo PDF al correo: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; revistaagricola@inifap.gob.mx.

Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial 4.0 Internacional.