Agrupamiento de trigos mediante sensores infrarrojos y fracciones de forraje en tres muestreos

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v13i1.2379Palabras clave:

forraje seco, fracciones de forraje, muestreos, NDVI, trigoResumen

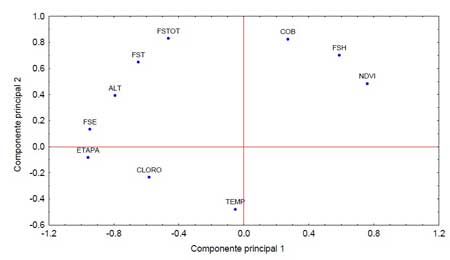

El trigo es un cultivo importante para la alimentación humana y una alternativa forrajera extraordinaria para el ganado. En México no se le cultiva específicamente con ese objetivo, pero se trabaja en la generación de genotipos con fines forrajeros auxiliándose de tecnología emergente. Se evaluaron 22 genotipos de trigo y tres testigos de otra especie en cuatro ambientes durante los ciclos otoño-invierno 2017-2018 y 2018-2019 mediante un diseño de bloques completos al azar con tres repeticiones, con el fin de agrupar genotipos a través de tres muestreos (a los 75, 90 y 105 días después de la siembra) y estimar la asociación entre variables. Con las medias de los genotipos a través de los ambientes se realizaron análisis de componentes principales y conglomerados para cada muestreo. Los resultados del análisis de varianza justificaron el estudiar los muestreos por separado. En cada muestreo se retuvieron hasta cinco grupos, existiendo grupos de trigos con rendimientos de forraje seco iguales o superiores al de la avena. En etapas tempranas se tuvo mayor proporción de hojas, las cuales disminuyeron al avanzar la etapa fenológica, mientras se incrementaba la fracción de espigas, con un leve decremento de la fracción de tallos. Existen grupos de trigos forrajeros que pueden representar una opción para sustituir la avena, sobresaliendo los trigos AN-229-09, AN-241-13, AN-268-99, AN-217-09 y AN-263-99. Se detectó una asociación positiva entre el NDVI, FSH y COB que perduró a través de los muestreos, sugiriendo que el uso de sensores infrarrojos puede emplearse en la estimación de materia seca de hojas.

Descargas

Citas

Arriaga, L.; Espinoza, J. M.; Aguilar, C.; Martínez, E.; Gómez, L. y Loa, E. 2000. Regiones terrestres prioritarias de México. Comisión nacional para el conocimiento y uso de la biodiversidad (CONABIO). 1ra. (Ed.). México, DF. 611 p.

Cabrera-Bosquet, L.; Molero, G.; Stellaci, A.; Bort, J.; Nogués, S. and Araus, J. 2011. NDVI as a potential tool for predicting biomass, plant nitrogen content and growth in wheat genotypes subjected to different water and nitrogen conditions. Hungary. Cereal Res. Comm. 39(1):147-159.

Colín, R. M.; Zamora, V. V. M.; Lozano del R, A. J.; Martínez, Z. G. y Torres, T. M. A. 2007. Caracterización y selección de nuevos genotipos imberbes de cebada forrajera para el norte y centro de México. México. Téc. Pec. Méx. 45(3):249-262.

Colín, R. M.; Zamora, V. V. M.; Torres, T. M. A. y Jaramillo, S. M. A. 2009. Producción y valor nutritivo de genotipos imberbes de cebada forrajera en el norte de México. Téc. Pec. Méx. 47(1):27-40.

Domínguez, M.; López, C. L. E.; Benítez, R. C. I. y Mejía, C. J. A. 2016. Desarrollo radical y rendimiento en diferentes variedades de trigo, cebada y triticale bajo condiciones limitantes de humedad del suelo. México. Terra Latinoam. 34(4):393-407. Gill, K. S. K.; Omokanye, A. T.; Pettyjohn, J. P. and Elsen, M. 2013. Evaluation of forage type barley varieties for forage yield and nutritive value in the peace region of Alberta. England. J. Agric. Sci. 5(2):24-36.

Manly, B. F. J. 1986. Multivariate statistical methods: a primer. Chapman and Hall. London-New York. London. 159 p.

Pask, A. J. D.; Pietragalla, J.; Mullan, D. M. and Reynolds, M. P. 2012. Physiological breeding II: a field guide to wheat phenotyping. Centro Internacional de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT). First (Ed.). DF, México. 133 p.

Reynolds, M. P.; Pask, A. J. D.; Mullan, D. M. y Chávez, D. P. N. 2013. Fitomejoramiento fisiológico I: enfoques interdisciplinarios para mejorar la adaptación del cultivo. Centro Internacional de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT). 1a (Ed.). México, DF. 174 p.

SAS. 1989. Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User’s guide. Version 6. Fourth edition. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. 943 p.

SAGARPA. 2017. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación planeación agrícola nacional 2017-2030. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment /file/256424/b-sico-avena.pdf.

SIACON. 2018. Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta. Producción nacional por cultivo. https://www.gob.mx/siap/acciones-y-programas/produccion-agricola-33119.

Shao, G. and Halpin, P. N. 1995 Climatic controls of eastern north American coastal tree and shrub distributions. USA. J. Biogeogr. 22(6):1083-1089.

Statistica, 1994. Statistica for windows (ver. 7). StatSoft, Inc. Tulsa Ok, USA.

Suaste, F. M. P.; Zamora, V. V. M.; Reyes, V. M. H.; Villaseñor, M. H. E.; Santacruz, V. S. A. y Moya, S. E. 2015. Agrupamiento de genotipos de la colección nacional de trigo en base a genes de interés agronómico. México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 6(4):695-706.

Torres, T. M. A.; Zamora, V. V. M.; Colin, R. M.; Foroughbakhch, P. R. y Ngangyo, H. M. 2019. Caracterización y agrupamiento de cebadas imberbes mediante sensores infrarrojos y rendimiento de forraje. México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 10(5):1125-1137.

Ward, J. H. 1963. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. USA. J. Am. Statistical Association. 58(301):236-244.

Wilson, G. C. Y.; Hernández, G. A.; Ortega, C. M. E.; López, C. C.; Bárcena, G. R.; Zaragoza, R. J. L. y Aranda, O. G. 2017. Análisis del crecimiento de tres líneas de cebada para producción de forraje, en el valle de México. Argentina. Rev. FCA Uncuyo. 49(2):79-92.

Zadocks, J. C.; Chang, T. T. and Konzak, C. F. 1974. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. UK. Weed Res. 14(12):415-421.

Zamora, V. V. M.; Lozano, R. A. J.; López, B. A.; Reyes, V. M. H.; Díaz, S. H.; Martínez, R. J. M y Fuentes, R. J. M. 2002. Clasificación de triticales forrajeros por rendimiento de materia seca y calidad nutritiva en dos localidades de Coahuila. Téc. Pec. Méx. 40(3):229-242.

Zamora, V. V. M.; Colin, R. M.; Torres, T. M. A.; Rodríguez, G. A y Jaramillo, S. M. A. 2016. Producción y valor nutritivo en fracciones de forraje de trigos imberbes. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 7(2):291-300.

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2022 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0.

Los autores(as) que publiquen en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas aceptan las siguientes condiciones:

De acuerdo con la legislación de derechos de autor, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas reconoce y respeta el derecho moral de los autores(as), así como la titularidad del derecho patrimonial, el cual será cedido a la revista para su difusión en acceso abierto.

Los autores(as) deben de pagar una cuota por recepción de artículos antes de pasar por dictamen editorial. En caso de que la colaboración sea aceptada, el autor debe de parar la traducción de su texto al inglés.

Todos los textos publicados por Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas -sin excepción- se distribuyen amparados bajo la licencia Creative Commons 4.0 atribución-no comercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 internacional), que permite a terceros utilizar lo publicado siempre que mencionen la autoría del trabajo y a la primera publicación en esta revista.

Los autores/as pueden realizar otros acuerdos contractuales independientes y adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión del artículo publicado en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (por ejemplo incluirlo en un repositorio institucional o darlo a conocer en otros medios en papel o electrónicos) siempre que indique clara y explícitamente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

Para todo lo anterior, los autores(as) deben remitir el formato de carta-cesión de la propiedad de los derechos de la primera publicación debidamente requisitado y firmado por los autores(as). Este formato debe ser remitido en archivo PDF al correo: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; revistaagricola@inifap.gob.mx.

Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial 4.0 Internacional.