Brosimum alicastrum: sexado, producción de flores, semillas y reguladores de crecimiento

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v14i4.3060Palabras clave:

ácido giberélico, árboles, citocininas, expresión sexualResumen

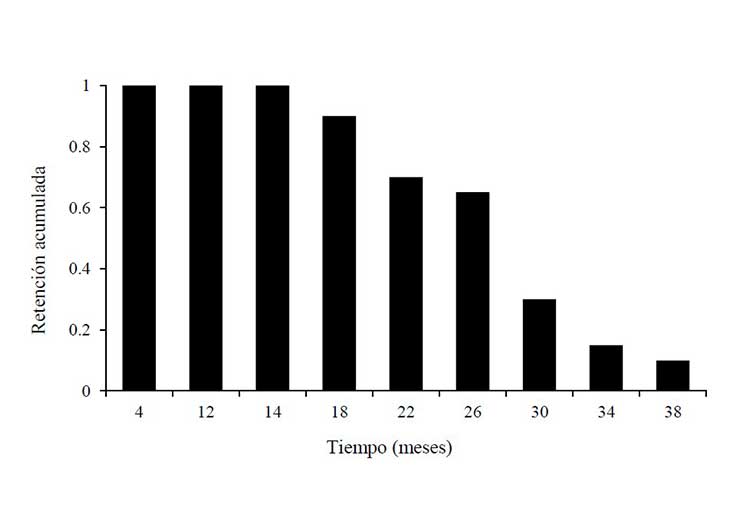

Brosimum alicastrum Swarts. (conocido localmente como ramón) es una especie del bosque tropical con importancia para el sector alimentario; por tanto, estudiar sus características fisio-técnicas es fundamental. Se determinó la proporción de sexos en tres poblaciones adultas del estado de Yucatán. La primera plantación comprendió un total de 312 individuos, 208 machos y 104 hembras; el segundo, 45 árboles masculinos y 29 femeninos (74 árboles) y el tercero, 41 machos y 29 hembras (70 árboles). En promedio, 64% de los árboles eran machos y 34% hembras. En una plantación separada (50 árboles) establecida ad hoc, 30% de los árboles comenzaron a producir flores siete años después del trasplante, 38% lo hicieron después de 8 años, 28% a los nueve años y 4% a los 10 años, 33 (66%) de los árboles eran machos y 17 (34%) hembras. El experimento comprendió de 2009 a 2019 y no se registraron cambios de sexo durante este tiempo. La producción media de semillas de árboles adultos fue de 145.6 kg árbol-1 año-1. Se realizó un experimento paralelo para dar seguimiento a la retención de hojas, éstas permanecieron en la copa durante más de 40 meses (1 217 días). Adicionalmente se midió el contenido de reguladores del crecimiento vegetal que podrían usarse como marcadores moleculares para seleccionar hembras. Los árboles hembras mostraron mayor contenido de ácido giberélico y citocininas que los árboles machos. La diferencia en el contenido de citocininas entre ambos sexos alcanzó 500%.

Descargas

Citas

Chen, Z. Y. and Tan, B. C. 2015. New insight in the Gibberellin biosynthesis and signal transduction. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 10(5):140-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15592324.2014.1000140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2014.1000140

CONABIO-PRONARE. 2014. Brosimum alicastrum Swartz. Serie Paquetes Tecnológicos. 1(1):1-6. http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/13/891Brosimum%20alicastrum.

Coste, S.; Roggy, J. C.; Schimann, H.; Epron, D. and Dreyer, E. 2011. A cost-benefit analysis of acclimation to low irradiance in tropical rainforest tree seedlings: leaf life span and payback time for leaf deployment. J. Exp. Bot. 62(11):3941-3955. http://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/err092. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/err092

Craven, J. D.; Dent, D. H; Braden, D. J; Ashton, M. S.; Berlyn, G. P. and Hall, J. S. 2011. Seasonal variability of photosynthetic characteristics influences growth of eight tropical tree species at two sites with contrasting precipitation in Panama. For. Ecol. Manag. 261(10):1643-1653. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.017

Davies, P. J. 2010. The plant hormones: their nature, occurrence, and functions. In: plant hormones: biosynthesis, signal transduction, action. Davies, P. J. 3ra. Ed. Springer. Dordrecht, Netherlands. 1-15 pp. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-2686-7_1

De León, D. M. M.; Legarreta, G. M. A.; Olivas, G. J. M.; Guerrero, M. S. y Baray, G. M. R. 2020. Análisis financiero y económico del cultivo del pistache en el Municipio de López, Chihuahua. Rev. Biológico-Agropecuaria Tuxpan. 8(2):14-22. https://doi.org/10.47808/ revistabioagro.v8i2.175.

Enrique, F. C. 2022. El castaño, un cultivo de alta rentabilidad en auge. Hifas Foresta. 1(1):1-13. https://www.hifasforesta.com/blog/rentabilidad-del-castano-el-castano-un-cultivo-de-alta-rentabilidad-en-auge.

Golenberg, E. M. and West, N. W. 2013. Hormonal interaction and gene regulation can link monoecy and environmental plasticity to the evolution of dioecy in plants. Am. J. Bot. 100(6):1022-1037. http://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1200544. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1200544

González, P. A. 1939. El ramón o capomo. Boletín platanero y agrícola. 2(12):221-222.

González, R. B. M. 2011. El Palacio de General Cantón, 100 años de historia. In: gaceta de museos. Museos y educación núm. 51 Tercera época. Ed. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Ciudad de México, México. 64 p.

Grijalva, C. R. L.; Macías, D. R.; López, C. A. y Robles, C. F. 2009. Productividad de cultivares de olivo para aceite (Olea europaea L.) bajo condiciones desérticas en Sonora. Biotecnia. 11(2):2-28. htpps: https://doi.org/10.18633/bt.v11i2.60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18633/bt.v11i2.60

Guo, S.; Zheng, Y.; Joung, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Crasta, R. O.; Sobral, W. B.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S. and Fei, Z. 2010. Transcriptome sequencing and comparative analysis of cucumber flowers with different sex types. BMC Genomics. 11(384):1-13. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-384. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-384

Hernández-González, O.; Vergara-Yoisura, S. y Larqué-Saavedra, A. 2015. Primeras etapas de crecimiento de Brosimum alicastrum Sw. en Yucatán. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Forest. 6(27):38-48. http://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v6i27.279. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v6i27.279

Khryanin, V. N. 2002. Role of phytohormones in sex differentiation in plants. Russian J. Plant Physiol. 49(1):545-551. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016328513153. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016328513153

Kikuzawa, K. and Lechowicz, M. J. 2011. Ecology of leaf longevity. Springer. Tokyo, Japan. 147 p. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-53918-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-53918-6

Kitajima, K.; Cordero, R. A. and Wright, J. J. 2013. Leaf life span spectrum of tropical woody seedlings: effects of light and ontogeny and consequences for survival. Ann. Bot. 112(4):685-699. http://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mct036. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mct036

López-Mata, L. 1987. Gynecological differentiation in provenances of Brosimum alicastrum a tree of moist tropical forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 21(3):197-208. http://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1127(87)90043-0. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1127(87)90043-0

Manzano, M. S.; Martínez, C. J.; García, M. M.; Megías, S. Z. and Jamilena, Q. M. 2014. Involvement of ethylene in sex expression and female flower development in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 85(1):96-104. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy. 2014.11.004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.11.004

Martín, A.; Troadec, C.; Boualem, A.; Rajab, M.; Fernández, M.; Morín, H.; Pitrat, M.; Dogimont, C. and Bendahmane, A. 2009. A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature. 461(7267):1135-1138. http://doi.org/10.1038/nature 08498. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08498

Martínez, M. M 1936. Plantas útiles de México. Ed. Botas. 2. Ciudad de México, México. 400 p.

Pardo-Tejeda, E. y Sánchez, M. C. 1980. Brosimum alicastrum, recurso silvestre tropical desaprovechado. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones sobre Recursos Bióticos. 1. Xalapa, Veracruz, México. 31 p.

Peters, C. M. and Pardo, T. E. 1982. Brosimum alicastrum (Moraceae): uses and potential in México. Econ. Bot. 36(1):166-175. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02858712. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02858712

Peters, C. M. 1989. Reproduction, growth and the population dynamics of Brosimum alicastrum Sw. in a moist tropical forest of Central Veracruz, Mexico. Ph. D. Dissertation. Yale University. New Haven, Connecticut, United States of America. 258 p.

Puleston, D. E. 1968. Brosimum alicastrum, as a subsistence alternative for the classic Maya of the central southern lowlands. Master of Arts Thesis. University of Pennsylvania. United States of America. 137 p.

Riefler, M.; Novak, O.; Strand, M. and Schmülling, T. 2006. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development and cytokinin metabolism. The Plant Cell. 18(1):40-54. https://doi.org/10. 1105/tpc.105.037796. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.037796

Sánchez, T. V.; Nieto, P. M. L. y Mendizábal, H. L. C. 2005. Producción de semillas de Pinus cembroides subsp. Orizabensis. Bailey de Altzayanca, Tlaxcala, México. Foresta Veracruzana. 7(1):15-20 p. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49770104.pdf.

Salazar-Laureles, M. E.; Soto-Hernández, M. R. and San Miguel-Chávez, R. 2021. Growth regulators detected in the tuberization of potato. Plants infected by Candidatus liberibacter and treated with salicylic acid and hydrogen peroxide. In: the potato crop: Management, production, and food security. 1. Ed. Nova Science Publishers. Hauppauge, New York, United States of America. 143-162 pp.

Subiria-Cueto, R.; Larqué-Saavedra, A.; Reyes-Vega, M. L.; Vázquez-Flores, A.; Santana-Contreras, L. E.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Núñez-Gastélum, J. A.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Corral-Avitia, A. Y. and Martínez-Ruiz, N. R. 2019. Brosimum alicastrum Sw.: an alternative to improve the nutritional properties and functional potential of the wheat flour. Foods. 8(12):613-631. htpps://doi:10.3390/foods8120613.

Tarango, R. S. H. 2012. Manejo del nogal pecanero con base en su fenología. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). 3. Cd. Delicias, Chihuahua, México. Folleto técnico núm. 24. 41 p.

Wang, W. Y.; Chen, W. H.; Hung, L. S. and Chang, P. S. 2002. Influence of abscisic acid on flowering in Phalaenopsis hybrida. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 40(1):97-100. htpps://doi.org/10.1016/S0981-9428(01)01339-0. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0981-9428(01)01339-0

Xiangqing, P.; Ruth, W. and Xuemin, W. 2010. Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude extracts by HPLC-Mass spectrometry. Nature Protocols. 5(1):986-992. htpps://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.37

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2023 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0.

Los autores(as) que publiquen en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas aceptan las siguientes condiciones:

De acuerdo con la legislación de derechos de autor, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas reconoce y respeta el derecho moral de los autores(as), así como la titularidad del derecho patrimonial, el cual será cedido a la revista para su difusión en acceso abierto.

Los autores(as) deben de pagar una cuota por recepción de artículos antes de pasar por dictamen editorial. En caso de que la colaboración sea aceptada, el autor debe de parar la traducción de su texto al inglés.

Todos los textos publicados por Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas -sin excepción- se distribuyen amparados bajo la licencia Creative Commons 4.0 atribución-no comercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 internacional), que permite a terceros utilizar lo publicado siempre que mencionen la autoría del trabajo y a la primera publicación en esta revista.

Los autores/as pueden realizar otros acuerdos contractuales independientes y adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión del artículo publicado en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (por ejemplo incluirlo en un repositorio institucional o darlo a conocer en otros medios en papel o electrónicos) siempre que indique clara y explícitamente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

Para todo lo anterior, los autores(as) deben remitir el formato de carta-cesión de la propiedad de los derechos de la primera publicación debidamente requisitado y firmado por los autores(as). Este formato debe ser remitido en archivo PDF al correo: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; revistaagricola@inifap.gob.mx.

Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial 4.0 Internacional.