Dry matter accumulation and partitioning in three varieties of amaranth

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v16i7.3874Keywords:

Amaranthaceae, grain yield, pseudocereal, total biomassAbstract

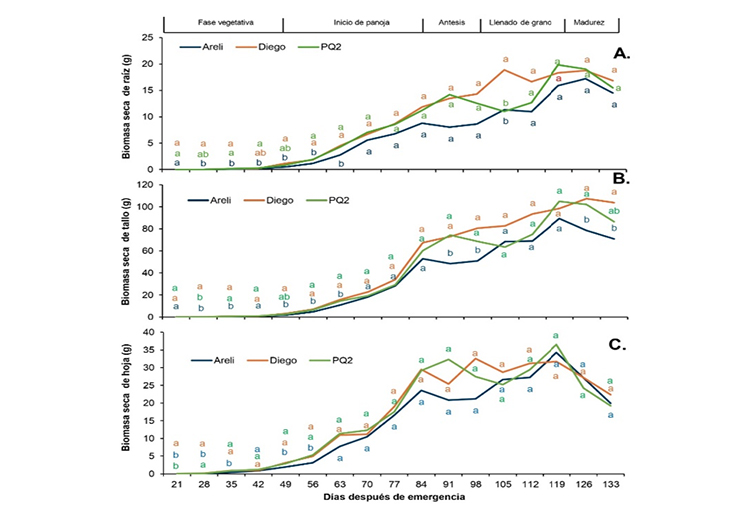

The revaluation of amaranth crops has a significant boom as a food of great value in human nutrition and a greater presence in the diet of the Mexican population and other countries. This study aimed to determine the dynamics of dry matter accumulation and partitioning by morphological organ in three varieties of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.): Areli, Diego and PQ2. An experiment was established in a completely randomized experimental design with four replications, under rainfed field conditions in the experimental field of Phytotechnics of the Chapingo Autonomous University, during the spring-summer cycle of 2023. From day 21 after the emergence, 17 whole plant samplings were performed every seven days, divided by organs and dried for the determination of dry biomass. The data were subjected to an analysis of variance (α= 0.05) and a comparison of means test (Tukey, α= 0.05). Of the total dry biomass, roots accounted for about 11%, stems ranged from 43 to 60%, and leaves made up about 32% of the total. Dry grain biomass accounted for about 11.2, 17.2 and 19% of total dry biomass in Areli, Diego and PQ2, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed in the development of the three varieties. Diego and PQ2 showed greater accumulation of dry matter compared to Areli, under limited soil moisture conditions caused by low precipitation during the cycle.

Downloads

References

Aguilar-Delgado, M. J.; Acosta-García, G.; Espitia-Rangel, E.; González-Chavira, M. M.; Lozano-Sotomayor, P.; Folter, S.; Sánchez-Segura, L.; Barrales-López, A. and Guevara-Olvera, L. 2018. Indeterminate and determinate growth habit in Amaranthus hypochondriacus. Agrociencia. 52(5):695-711. https://agrociencia-colpos.org/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1698.

Aguilera-Cauich, E. A.; Solís-Fernández, K. Z.; Ibarra-Morales, A.; Cifuentes-Velásquez, R. y Sánchez-del Pino, I. 2021. Amaranto: distribución y diversidad morfológica del recurso genético en partes de la región Maya sureste de México, Guatemala y Honduras. Acta Botánica Mexicana. 128:1-14. https://doi.org/10.21829/abm128.2021.1738.

Barrales-Domínguez, J. S.; Barrales-Brito, E. y Barrales-Brito, E. 2010. Amaranto: recomendaciones para su producción. Plaza y Valdés. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UAC). Fundación Produce Tlaxcala, AC. 168 p.

Cai, F.; Mi, N.; Ming, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X. and Zhang, B. 2023. Responses of dry matter accumulation and partitioning to drought and subsequent rewatering at different growth stages of maize in Northeast China. Frontiers in Plant Science. 14:1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1110727.

Espitia-Rangel, E. 2012. Amaranto: ciencia y tecnología. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Celaya, Guanajuato, México. 384 p.

Jarma-Orozco, A.; Cardona, A. C. y Araméndiz, T. H. 2012. Efecto del cambio climático sobre la fisiología de las plantas cultivadas: una revisión. Revista UDCA. Actualidad y Divulgación Científica. 15(1):63-76. https://doi.org/10.31910/rudca.v15.n1.2012.803.

León-Burgos, A. F.; Beltrán-Cortes, G. Y.; Barragán-Pérez. A. L. and Balaguera-López, H. E. 2021. Distribution of photoassimilates in sink organs of plants of Solanaceas, tomato and potato. A review. Ciencia y Agricultura. 18(3):79-97. https://doi.org/10.19053/01228420.v18.n3.2021.13566.

Lustre-Sánchez, H. 2022. Los superpoderes de las plantas: los metabolitos secundarios en su adaptación y defensa. Revista Digital Universitaria. 23(2):1-8. https://doi.org/10.22201/cuaieed.16076079e.2022.23.2.10.

Martínez-González, M. E.; Balois-Morales, R.; Alia-Tejacal, I.; Cortes-Cruz, M. A.; Palomino-Hermosillo, Y. A. y López-Guzmán, G. G. 2017. Postcosecha de frutos: maduración y cambios bioquímicos. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 19(esp):4075-4087. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i19.674.

Martínez-Salvador, L. 2016. Seguridad alimentaria, autosuficiencia y disponibilidad del amaranto en México. Problemas del Desarrollo. 47(186):107-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpd.2016.08.004.

Matías-Luis, G.; Hernández-Hernández, B. R.; Peña-Caballero, V.; Torres-López, N. G., Espinoza-Martínez, V. A. y Ramírez-Pacheco, L. 2018. Usos actuales y potenciales del amaranto (Amaranthus spp.). Journal of Negative and No Positive Results. 3(6):423-436. https://doi.org/10.19230/jonnpr.2410.

Monroy-Pedroza, D.; Martínez-Hernández, J. J.; Gavi-Reyes, F.; Torres-Aquino, M. y Hernández-Ríos, I. 2021. Crecimiento, acumulación y distribución de materia seca en dos cultivares de amaranto (Amaranthus hypochondriacus y A. cruentus) bajo fertigación. Biotecnia. 23(3):14-21. https://doi.org/10.18633/biotecnia.v23i3.1399.

Murray-Tortarolo, G. N. 2021. Seven decades of climate change across Mexico. Atmósfera. 34(2):217-226. https://doi.org/10.20937/ATM.52803.

Riggins, C. W.; Barba-Rosa, A. P.; Blair, M. W. and Espitia-Rangel, E. 2021. Editorial. Amaranthus: naturally stress-resistant resources for improved agriculture and human health. Frontiers in Plant Science. 12:1-13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.726875.

Romero-Romano, C. O.; Ocampo-Mendoza, J.; Sandoval-Castro, E.; Navarro-Garza, H.; Franco-Mora, O. y Calderón-Sánchez, F. 2017. Fertilización orgánica-mineral del cultivo de amaranto (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.). Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 8(12):1759-1771. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i8.700.

Rosado-Souza, L.; Yokoyama, R.; Sonnewald, U. and Fernie, A. R.2023. Understanding source-sink interactions: progress in model plants and translational research to crops. Molecular Plant. 16(1):96-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2022.11.015.

Salvador-Martínez, G.; Ortiz-Torres, E.; Guerrero-Rodríguez, J. D.; Taboada-Gaytán, O. R.; Herrera-Corredor, J. A. y Gómez-Aldapa, J. A. 2024. Características composicionales de especies de amaranto utilizadas como verdura. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 15(8):e3094. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v15i8.3094.

SAS Institute. 2010. STAT-SAS, Version 9.4. SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA.

SNICS. 2019. Servicio Nacional de Inspección y Certificación de Semillas. Innovaciones Vegetales. SNICS: Ciudad de México. 2-3 pp. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/545892/cat-innocaciones-veg-new.pdf.

Taiz, L.; Moller, I. M.; Murphy, A. and Zeiger, E. 2023. Plant physiology and development. Seventh Ed. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA. 752 p.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.