Nutraceutical analysis of fig cv. Nezahualcóyotl dehydrated by osmo-convection

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v16i6.3794Keywords:

Ficus carica L., bioactive compounds, cv. Nezahualcóyotl, osmosisAbstract

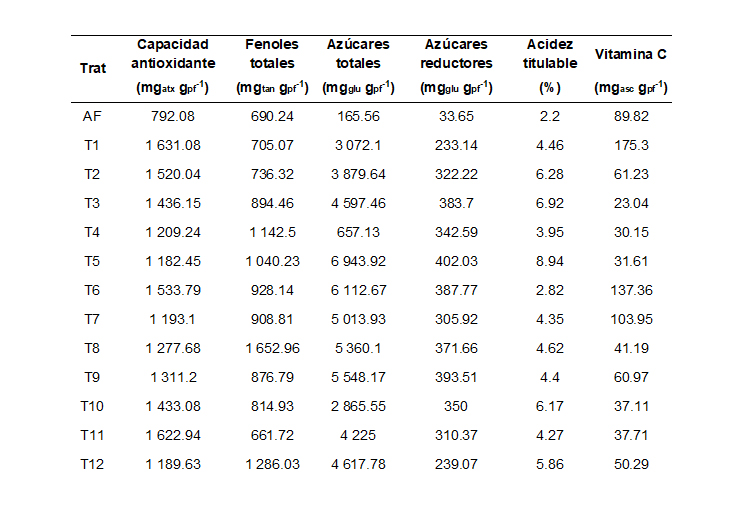

This research aimed to analyze the nutraceutical properties of fig (Ficus Carica L.) cv. Nezahualcóyotl dehydrated by osmo-convection. Due to the limited information on this variety in Mexico, the impact of the dehydration method on the bioactive compounds of the fruit was evaluated. The study was conducted in Texcoco, State of Mexico in 2024, using 120 fig plants under organic production. Thirty-six fruits were randomly taken and subjected to osmotic dehydration with sucrose concentrations of 0, 40, 50 and 60%, followed by convective dehydration at temperatures of 50, 60 and 70 °C. A completely randomized design was established, where the data were analyzed through Anova, Duncan tests or Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests according to the nature of the variables. The results showed that figs osmotically dehydrated with sucrose concentrations of 40-50% and convective temperatures of 50-60 °C presented the highest retention of total phenols, reaching values of up to 1 652.96 mg tannins g-1 fresh weight. In addition, antioxidant capacity increased by 54% compared to fresh figs, whereas vitamin C underwent significant degradation at temperatures above 60 °C. These findings provide information on the Nezahualcóyotl fig variety and suggest that the combination of osmotic and convective dehydration is an effective strategy to conserve and enhance nutraceutical properties that can have an agro-industrial and commercial impact.

Downloads

References

Andreou, V.; Thanou, I.; Giannoglou, M.; Giannakourou, M. C. and Katsaros, G. 2021. Dried Figs Quality Improvement and process energy savings by combinatory application of osmotic pretreatment and conventional air drying. Foods. 10(8):2-8. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081846.

Bezerra Pessoa, T. R.; Lima, A. G. B.; Martins, P. C.; Pereira, V. C.; Alves, T. C. O.; Silva, E. S. and Lima, E. S. 2021. Osmo-convective dehydration of fresh foods: theory and applications to cassava cubes. In: Delgado, J. M. P. Q. and Barbosa, de L. A. G. Ed. Transport Processes and Separation Technologies. 151-183 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47856-8-6.

de Mello Jr, R. E.; Corrêa, J. L. G.; Lopes, F. J.; de Souza, A. U. and da Silva, K. C. R. 2019. Kinetics of the pulsed vacuum osmotic dehydration of green fig (Ficus carica L.). Heat and Mass Transfer. 55(6):1685-1691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-018-02559-w.

Fernandes, F. A. N.; Linhares, F. E. and Rodrigues, S. R. 2008. Ultrasound as pre-treatment for drying of pineapple. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 15(6):1049-1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.03.009.

Fernandez, J. I. 2016. Caracterización química y morfológica de ocho ecotipos de higo (Ficus carica L.). 1-10 pp. http://ri.uaemex.mx/handle/20.500.11799/65163.

Fernández-Pavía, Y. L.; García-Cue, J. L.; Fernández-Pavía, S. P. y Muratalla-Lua, A. 2020. Deficiencias nutrimentales inducidas en higuera cv. Neza en condiciones hidropónicas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 11(3):581-592. https://cienciasagricolas.inifap.gob.mx/index.php/agricolas/article/view/2073.

Hosseini, E.; Tsegay, Z. T.; Smaoui, S. and Varzakas, T. 2024. Chemical structure, composition, bioactive compounds, and pattern recognition techniques in figs (Ficus carica L.) quality and authenticity: an updated review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. v.137, 106863. 10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106863.

Hajam, T. A. and Saleem, H. 2022. Phytochemistry, biological activities, industrial and traditional uses of fig (Ficus carica): a review. Chemico-Biological Interactions. v. 368, 110237, 2-4 pp. 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110237.

INTAGRI. 2020. Producción de higo en México. Intagri S.C. www.inagri.com. https://www.intagri.com/articulos/frutales/produccion-de-higo-en-mexico.

Landim, A. P. M.; Barbosa, M. I. M. J. and Júnior, J. L. B. 2016. Influence of osmotic dehydration on bioactive compounds, antioxidant capacity, color and texture of fruits and vegetables: a review. Ciência Rural. 46(10):1714-1722. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20150534.

Lansky, E. P. and Paavilainen, H. M. 2010. Figs: the genus ficus. In: figs: the genus Ficus. 366 p. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420089677.

Lee, S. K. and Kader, A. A. 2000. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 20(3):207-220. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925521400001332.

López, E. J.; Uribe, U. E.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Miranda, H. M.; Vergara, J. J.; Gonzalez, M. E. and Di Scala, K. C. 2010. Effect of air temperature on drying kinetics, vitamin c, antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, non-enzymatic browning and firmness of blueberries variety o´neil. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 3(5):772-777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-009-0306-8.

Mandala, I. G.; Anagnostaras, E. F. and Oikonomou, C. K. 2005. Influence of osmotic dehydration conditions on apple air-drying kinetics and their quality characteristics. Journal of Food Engineering. 69(3):307-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.08.021.

Moustafa, S. E.; Abed-Hakim, H. I. and Maatouk, H. I. 2016. Osmotic dehydration of fig and plum. Egyptian Journal of Agricultural Research. 94(4):905-921. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejar.2016.153140.

Pandidurai, G. and Vennila, P. 2020. Processing, value addition and effect of nutritional quality of fig fruit by osmatic dehydration. International Journal of Chemical Studies. 8(4):3644-3647. https://doi.org/10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i4at.10213.

SIAP. 2023. Sistema de información agroalimentaria y pesquera. Higo. 1 p. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/874025/Higo-monografi-a-2023.pdf.

Slatnar, A.; Klancar, U.; Stampar, F. and Veberic, R. 2011. Effect of drying of figs (Ficus Carica L.) on the contents of sugars, organic acids, and phenolic compounds. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 59(21):11696-11702. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf202707y.

Vega-Gálvez, A.; Palacios, M. P.; Boglio, H. F.; Pássaro, C. C.; Jeréz, M. C. y Lemus-Mondaca, R. 2007. Deshidratación osmótica de la papaya chilena (Vasconcellea pubescens) e influencia de la temperatura y concentración de la solución sobre la 15 de transferencia de materia. Food Science and Technology. 27(3):470-477. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-20612007000300008.

Yadav, R. K. and Dubey, R. S. 2019. Sulfur-induced oxidative stress in crop plants: Responses and tolerance mechanisms. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 14(5):1568974. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15476286.2019.1568974.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.