Optimizing corn trade routes in Mexico using linear programming

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v15i8.3535Keywords:

corn trade, corn transportation costs, efficient agricultural markets, national strategic corn reserve, storage capacityAbstract

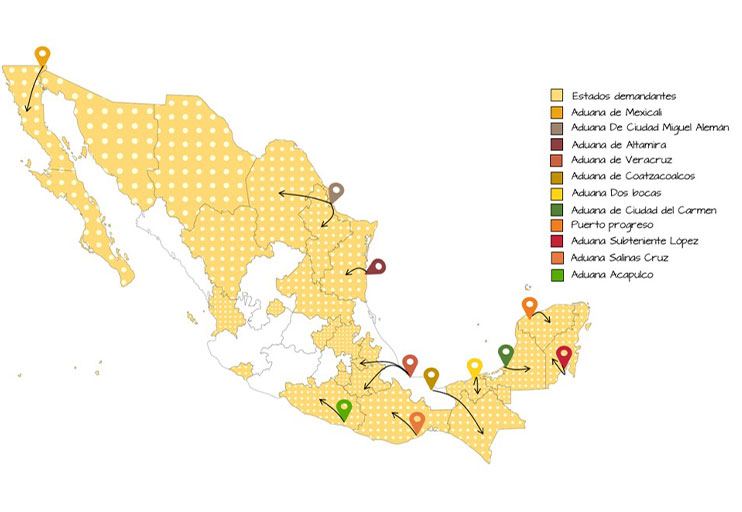

Corn is one of the most important foods in the diet of Mexicans; there was a sustained growth in imports since the trade opening of Mexico since 1994 with the entry into force of NAFTA; imports have grown to such a degree that, in 2021, Mexico was the world’s second largest importer of corn with 17.4 million tons, only after China. This research aimed to determine the corn transport routes during 2020 through linear programming, minimizing their distances to meet the demands of each destination in two scenarios: a supposed closed economy and the current open economy with global exchanges. The optimal national distribution routes that together imply the shortest transport distances were determined for both scenarios. For the closed economy scenario, seven states of origin and 25 states demanding corn were identified. In the open economy, a total of 49 suppliers were proposed for the same 25 destinations. It was concluded that Mexico is commercially dependent on corn imports for 37% of its total consumption; due to the logistical challenge of minimizing the distances traveled for transportation, obtaining an optimal allocation implies an improvement in social welfare at the country level, easily tangible in the improvement of the final price of corn.

Downloads

References

ASERCA. 2018. Agencia de Servicios a la Comercialización y Desarrollo de Mercados Agropecuarios. Maíz grano cultivo representativo de México. Gobierno gob.mx. https://www.gob.mx/aserca/articulos/maizgranocultivorepresentativodemexico?idiom=es.

Bustamante-Muñoz, P. F. 2015. Comparación de métodos de estimación del consumo aparente de carne de cerdo. Tesis de licenciatura. 1-2 pp. https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/136975.

CEDRSSA. 2019. Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberanía Alimentaria. Producción de granos básicos y suficiencia alimentaria 2019-2024.

Dantzig, G. B. y Thapa, M. N. 1997. Linear programming, 1: introduction Ed. Springer. https://www.academia.edu/19935874/GeorgeBDantzigMukundNThapaLinearProgramming1Introduction. 13-15 pp.

Del Río-Gómez, D. 2021. Un método simplex en programación lineal multiobjetivo. Trabajo de grado en Matemáticas. Universidad de Valladolid. 27-28 pp. https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/50558.

Díaz-Parra, O. y Cruz-Chávez, M. A. 2006. El problema del transporte. Reporte técnico. http://www.gridmorelos.uaem.mx/~mcruz/surveykoko.pdf.

Dorta-González, P.; Santos-Peñate, D. R. y Suárez-Vega, R. 2001. Una experiencia práctica de programación matemática con LINGO. Revista Electrónica de Comunicaciones y Trabajos de Asepuma. 9(1):1-11.

FAO. 2010. Food and Agriculture Organization. El estado de la inseguridad alimentaria en el mundo: la inseguridad alimentaria en crisis prolongadas. FAO. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/71d32269-34ed-48c5-9983-e928e20b214d/contente.

FAOSTAT. 2024. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (Banco de datos). Datos sobre alimentación y agricultura (FAOSTAT). https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/TM.

García-Salazar, J. A. y Santiago-Cruz, M. J. 2004. Importaciones de maíz en México: un análisis espacial y temporal. Investigación Económica. 63(250):131-160.

González-Estrada, A. y Alferes-Varela, M. 2010. Competitividad y ventajas comparativas de la producción de maíz en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 1(3):381-396. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci-arttext&pid=S2007-09342010000300008&lng=es&tlng=es.

MapChart. 2020. México. MapChart. https://www.mapchart.net/mexico.html#.

Martínez-Jiménez, D. D.; Castillo-Altamirano, M.; Núñez-Betancourt, E. Y. and Luqués Gaitán, C. E. 2023. Analysis of national and international tomato trade routes through the simplex method. Agro Productividad. https://doi.org/10.32854/agrop.v16i5.2428.

Moncayo-Martínez, L. A. y Muñoz, D. F. 2018. Un Sistema de apoyo para la enseñanza del método simplex y su implementación en computadora. Formación Universitaria. 11(6):29-40. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062018000600029.

Moreno-Sáenz, L. I.; González-Andrade, S. y Matus-Gardea, J. A. 2016. Dependencia de México a las importaciones de maíz en la era del TLCAN. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 7(1):115-126.

Pérez-Solís, I. 2021. Conoce a profundidad al grano más importante de México en “Tierra de Maíces”. https://ciencia.unam.mx/leer/1133/conoce-a-profundidad-al-grano-mas-importante-de-mexico-en-tierra-de-maices.

Rubio, B. 1987. Resistencia campesina y explotación rural en México. Primera edición. https://ru.iis.sociales.unam.mx/handle/IIS/2898.

Saad, I. 2004. Maíz y libre comercio en México. Revista Claridades Agropecuarias. 127:44-48.

SADER. 2024. Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. https://www.gob.mx/agricultura.

Sánchez-Galván, F.; Garay-Rondero, C. L.; Mora-Castellanos, C.; Gibaja-Romero, D. E. y Bautista-Santos, H. 2017. Optimización de costos de transporte bajo el enfoque de teoría de juegos. Estudio de caso. Nova Scientia. 9(19):185-210. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=203353519012.

Schwentesius, R. y Ayala-Garay, A. V. 2014. Seguridad y soberanía alimentaria en México: análisis y propuestas de política. Primera edición. Ed.http://biblioteca.dicea.chapingo.mx/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=13004&shelfbrowse-itemnumber=27688.

SEGALMEX. 2024. Seguridad Alimentaria Mexicana. https://www.gob.mx/segalmex.

SIAP. 2024. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. https://www.gob.mx/siap/.

Tejeda-Villanueva, A.; Blanco-Jiménez, M. y Guerra-Moya, S. 2019. Factores que impulsan las importaciones de las empresas de alimentos procesados, mejorando su competitividad. Investigación Administrativa. 48(124):1. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=456059299007.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.