Baking and cookie quality of mixtures of whole amaranth flour and refined wheat flour

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v13i8.3162Keywords:

baking quality, cookie quality, refined wheat flour, whole amaranth flourAbstract

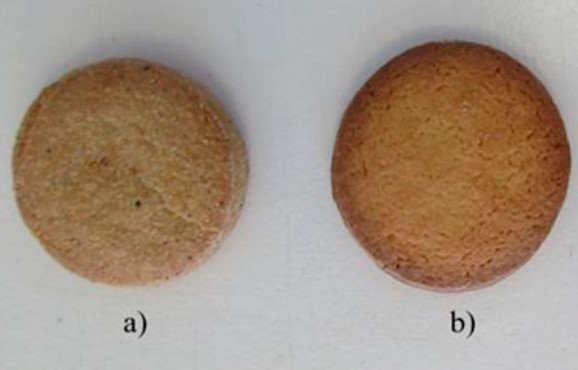

The imbalance between excessive intake and energy expenditure due to the consumption of refined carbohydrates and fats can be associated with overweight and obesity, causing a public health problem as currently happens in Mexico. Refined flour of bread wheat in the form of sweet bread and cookies are part of this intake. An alternative to this problem is the substitution in the making of these products for flour of whole grains, such as amaranth, for which the dough, as well as its baking and cookie quality must be characterized. Therefore, the objective of the present research was to evaluate the rheological characteristics of the dough, volume of bread and cookie factor of mixtures of whole amaranth flour and refined wheat flour. The whole amaranth flours were obtained from the lines called opaca and cristalina and the refined wheat flour from the varieties Fuertemayo F2016 and Urbina S2007. The mixtures with 5, 10 and 15% whole flour of opaca and cristalina amaranth decreased the strength and increased the tenacity of the dough, consequently they decreased the volume of bread and showed crumbs brown in color and with poor texture. On the other hand, mixtures with 25% whole flour of opaca and cristalina amaranth, as well as that of 75% whole flour of cristalina amaranth exceeded the cookie factor of the control variety 100% refined wheat flour, while the rest of the combinations were classified as very good for their cookie factor greater than 4.5. Based on the above, the substitution of whole amaranth flour does not decrease the cookie factor, so it is recommended to use it in mixtures with refined wheat flour, without detracting from the cookie yield, the opposite in the making of bread, where it decreased its volume and therefore the bread yield.

Downloads

References

Álvarez, J. L.; Auty, M.; Arendt, E. K. and Gallagher, E. 2010. Baking properties and microstructure of pseudocereal flours in gluten-free bread formulations. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 230(3):437-445.

AACC. 2005. American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods of the AACC. 9th (Ed.). American Association of Cereal Chemists. St. Paul, MN, USA.

Ayala, G. A. V.; Espitia, R. E.; Altamirano, C. J. R.; Rocío, I. P. A.; González, M. L.; Muñiz, R. E. y Almaguer, V. G. 2020. Factores que favorecen el consumo de amaranto en la Ciudad de México: caso de estudio Xochimilco. Textual. 75(8):75-99.

Ayo, J. A. 2001. The effect of amaranth grain flour on the quality of bread. Int. J. Food Prop. 4(2):341-351.

Bhat, A.; Satpathy, G. and Gupta, R. K. 2015. Evaluation of Nutraceutical properties of Amaranthus Hypochondriacus L. grains and formulation of value-added cookies. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 3(5):51-54.

CANIMOLT. 2016. Cámara Nacional de la Industria Molinera de Trigo. Reporte estadístico 2015 con datos de 2016. https://issuu.com/canimolt/docs/reporte-estadi-stico-2015-2016.

Coțovanu, I. and Mironeasa, S. 2021. Impact of different amaranth particle sizes addition level on wheat flour dough rheology and bread features. Foods. 10(7):1-19.

Czerwin’ski, J.; Bartnikowska, E.; Leontowic, H.; Lange, E.; Leontowicz, M.; Katrich, E.; Trakhtenberg, S. and Gorinstein, S. 2004. Oat (Avena sativa L.) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) meals positively affect plasma lipid profile in rats fed cholesterolcontaining diets. J. Nutr. Biochem. 15(10):622-629.

Denova, G. E.; Castañón, S.; Talavera, J. O.; Gallegos, C. K.; Flores, M.; Dosamantes, C. D. and Salmerón, J. 2010. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in an urban Mexican population. J. Nutr. 140(10):1855-1863.

García, G. E.; De la Llata, R. M.; Kaufer, H. M.; Tusié, L. M.T.; Calzada, L. R.; Vázquez, V. V.; Barquera, C. S.; Caballero, R. A. J.; Orozco, L.; Velásquez, F. D.; Rosas, P. M.; Barriguete, M. A.; Zacarías, C. R. y Sotelo, M. J. 2008. La obesidad y el síndrome metabólico como problema de salud pública. Una reflexión. Arch. cardiol. Méx. 78(3):318-337.

Huerta, O. J. A.; Maldonado, C. E. y Barba de la R. A. P. 2012. Amaranto: propiedades benéficas para la salud. In: Espitia, R. E. (Ed.). Amaranto: ciencia y tecnología. Libro científico núm. 2. INIFAP/SINAREFI. México. 303-312 pp.

Joshi, D. C.; Sood, S.; Hosahatti, R.; Kant, L.; Pattanayak, A.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, D. and Stetter, M. G. 2018. From zero to hero: the past, present and future of grain amaranth breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131(9):1807-1823.

Nash, D.; Lanning, S. P.; Fox, P.; Martin, J. M.; Blake, N. K.; Souza, E.; Graybosch, R. A.; Giroux, M. J. and Talbert, L. E. 2006. Relationship of dough extensibility to dough strength in a spring wheat cross. Cereal Chem. 83(3):255-258.

Man, S.; Păucean, A.; Muste, S.; Chiș, M. S.; Pop, A. and Călian, I. D. 2017. Assessment of amaranth flour utilization in cookies production and quality. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 23(2):97-103.

Miranda, R. K. C.; Sanz, P. N. and Haros, C. M. 2019. Evaluation of technological and nutritional quality of bread enriched with amaranth flour. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 114(11):1-12.

Olvera, M. S. 2022. Sobre la intervención nutricional y alimentaria en la diabetes mellitus. Rev. Cuba. Aliment. Nutr. 30(2):135-152.

Sanz, P. J. M.; Wronkowska, M.; Soral, S. M. and Haros, M. 2013. Effect of whole amaranth flour on bread properties and nutritive value. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 50(3):679-685.

Shamah, L. T.; Vielma, O. E.; Heredia, H. O.; Romero, M. M.; Mojica, C. J.; Cuevas, N. L.; Santaella, C. J. A. y Rivera, D. J. 2020. Encuesta nacional de salud y nutrición 2018-2019: resultados nacionales. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Cuernavaca, Morelos, México. 186-243 pp.

Sindhuja, A.; Sudha, M. L. and Rahim, A. 2005. Effect of incorporation of amaranth flour on the quality of cookies. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 221(5):597-601.

SIAP. 2020. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Panorama Agroalimentario 2020. https://www.inforural.com.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Atlas-Agroalimentario-2020.pdf.

Vásquez, L. F.; Verdú, A. S.; Islas, A. R.; Barat, B. J. M. y Grau, M. R. 2016. Efecto de la sustitución de harina de trigo con harina de quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) sobre las propiedades reológicas de la masa y texturales del pan. Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Postcos. 17(2):307-317.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.