Handling of ‘Kent’ mango destined for the market as a fruit to eat

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v13i27.3158Keywords:

Mangifera indica, ripening degree, shipping temperatureAbstract

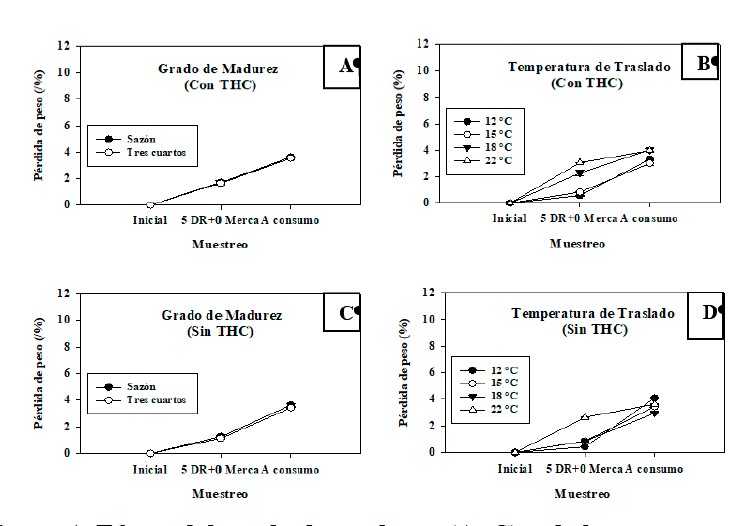

The increase in demand for ready-to-eat ripe mango opens up an interesting possibility for mango producers in Mexico due to the geographical proximity of production sites to U.S. markets. The key aspects in the production of ripe mango to eat are: maturity at harvest, requirement or not of hydrothermal quarantine treatment (HQT), temperature and duration of refrigerated transport, as well as handling during commercialization. The work was carried out in an area with and without the presence of fruit flies, as well as with and without requirement of HQT (Nayarit and northern Sinaloa, respectively). States of maturity at harvest (mature and ¾ fruit), refrigeration temperatures (12, 15, 18 and 22 °C), with or without HQT were evaluated. The variables analyzed were weight loss, pulp color, pulp firmness, total soluble solids (TSS), titratable acidity and °Bx/acidity ratio. It was found that the degree of maturity at harvest was not so impactful in most of the variables, while the temperature of transport had a significant impact on most of them. At lower temperatures, greater firmness, lower weight loss and slow development of TSS, as well as longer shelf life. The temperature of 12 °C showed measurements similar to 15 and 18 °C at consumption in all the variables evaluated, in addition to being the temperature with the highest shelf life. HQT led to up to two days less shelf life compared to fruits without HQT.

Downloads

References

AOAC, 1984. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official methods of analysis. 14th (Ed). Association of Official Analytical Chemists Inc. Arlington, VA. USA. 1006.

Baloch, M. K. and Bibi, F. 2012. Effect of harvesting and storage conditions on the postharvest quality and shelf life of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit. South Afr. J. Bot. 83:109-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2012.08.001

Brecht, J. K.; Sargent, S. A.; Kader, A. A.; Mitcham, E. J.; Maul, F.; Brecht, P. E. and Menocal, O. 2017. Mango postharvest best management practices manual. National Mango Board. 40-44 pp.

Dea, S.; Brecht, J. F.; Nunes, M. C. N. and Baldwin, E. A. 2010. Occurrence of chilling injury in fresh-cut ‘Kent’ mangoes. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 57(1):61-71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.02.005

Djioua, T.; Charles, F.; Lopez, L. F.; Filgueiras, H.; Coudret, A.; Murillo, F.; Ducamp, C. M. N. and Sallanon, H. 2009. Improving the storage of minimally processed mangoes (Mangifera indica L.) by hot water treatments. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 52(2):221-226. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.10.006

Fallik, E. 2004. Prestorage hot water treatments (immersion, rinsing and brushing). Postharv. Biol, Technol. 32(2):125-134. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2003.10.005

Galviz, J. A.; Arjona, H.; Fischer, G.; Landwehr, T. y Martínez, R. 2002. Influencia de la temperatura y tiempo de almacenamiento en la conservación de fruto de mango (Mangifera indica L.) variedad Van Dyke. Agron. Colomb. 19(1-2):23-35.

García, M. R.; López, J. A.; Saucedo, V. C.; Salazar, G. S. y Suárez, E. J. 2015. Maduración y calidad de frutos de mango ‘Kent’ con tres niveles de fertilización. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 6(4):665-678. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v6i4.610

Ghasemnezhad, M.; Marshal, K.; Shilton, R.; Babalar, M. and Woolf, A. 2008. Effect of hot water treatments on chilling injury and heat damage in ‘satsuma’ mandarins: antioxidants enzymes and vacuolar ATPase, and pyrophosphatase. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 48(3):364-371. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.09.014

Henriquez, C.; González, R. y Krarup, C. 2005. Tratamientos térmicos y progresión del daño por enfriamiento y de la pigmentación de tomates en postcosecha. Ciencia e Investigación Agraria. 32(2):113-122.

Jacobi, K. K.; MacRae, E. A. and Hetherington, S. E. 2000. Effects of hot air conditioning of ‘Kensington’ mango fruit on the response to hot water treatment. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 21(1):39-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00163-0

Kader, A. A. 1992. Postharvest technology of horticultural crops 2nd (Ed.). UC Publication 3311. University of California, division of agriculture and natural resources, Oakland, California 94608. 39-48 pp.

Kim, Y.; Brecht, J. K. and Talcott, S. T. 2007. Antioxidant phytochemical and fruit quality changes in mango (Mangifera indica L.) following hot water immersion and controlled atmosphere storage. Food Chem. 105(4):1327-1334. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.03.050

Kim, Y.; Lounds, S. A. J. and Talcott, S. T. 2009. Antioxidant phytochemical and quality changes associated with hot water immersion treatment of mangoes (Mangifera indica L.). Food Chem. 115(3):989-993. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.019

Liu, L.; Wei, Y.; Shi, F.; Liu, C.; Liu, X. and Ji, S. 2015. Intermittent warming improves postharvest quality of bell peppers and reduces chilling injury. Postharv. Biol Technol. 101:18-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.11.006

Luna-Esquivel, G.; Arévalo-Galarza, M. L.; Anaya-Rosales, S.; Villegas-Monter, A.; Acosta-Ramos, M. y Leyva-Ruelas, G. 2006. Calidad de mango “Ataulfo” sometido a tratamiento hidrotérmico. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana. 29(2): 123-128.

Osuna, G. J. A.; Cáceres, M. I.; Montalvo, G. E.; Mata, M. O. M. y Tovar, G. B. 2007. Efecto del 1-Metilciclopropeno (MCP) y tratamiento hidrotérmico sobre la fisiología y calidad del mango ‘Keitt’. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 13(2):157-163. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5154/r.rchsh.2007.02.014

Osuna, G. J. A.; Nolasco, G. Y.; Gómez, J. R. y Pérez, B. M. H. 2019. Temperaturas de refrigeración para el envío de mangos ‘Kent’ y ‘Keitt’ hacia mercados distantes. Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Postc. 20(1): 26-35.

Paull, R. E. and Chen, N. J. 2000. Heat treatment and fruit ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 21(1):21-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00162-9

Pérez, B.; Bringas, E.; Cruz, L. y Baez, S. R. 2005. Evaluación de cera comestible en mango ‘Tommy Atkins’ destinado a la comercialización para el turismo parte I: efecto en las características fisicoquímicas. Iberoam. Tecnol. Postc. 7(1):24-32.

SAGARPA. 2018. Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Vigilancia epidemiológica de moscas. Exóticas de la fruta. Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASICA). https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/402359/ NAYARIT.pdf.

Siller, C. J.; Muy, R. D.; Báez, S. M.; Araiza, L. E. y Ireta, O. A. 2009. Calidad postcosecha de cultivares de mango de maduración temprana, intermedia y tardía. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 32(1):45-52.

Sripong, K.; Jitareerat, P.; Tsuyumu, S.; Uthairatanakij, A.; Srilaong, V.; Wongs A. C.; Ma, G.; Zhang, L. and Kato, M. 2015. Combined treatment with hot water and UV-C elicits disease resistance against anthracnose and improves the quality of harvested mangoes. Crop Protec. 77:1-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.07.004

Ummarat, N.; Matsumoto, T. K.; Wall, M. M. and Seraypheap, K. 2011. Changes in antioxidants and fruit quality in hot water-treated ‘Hom Thong’ banana fruit during storage. Sci. Hortic. 130(4):801-807. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2011.09.006

USDA. 2018. Foreign agricultural service. Three years trends for US. mango imports. http://www.fas.usda.gov.

Woolf, A. B. and Lay, Y. M. 1997. Pretreatments at 38 ºC of ‘Hass’ avocado confer thermotolerance to 50ºC hot water treatments. HortScience. 32(4):705-708.

Yahia, E. E. and Campos, J. P. 2000. The effect of hot water treatment used for insect control on the ripening and quality of mango fruit. Acta Hortic. 509(58):495-501. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2000.509.58

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.