Chemical compounds of Tagetes lucida essential oil and effects against Botrytis cinerea

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v16i3.3613Keywords:

Tagetes lucida, B. cinerea, essential oilAbstract

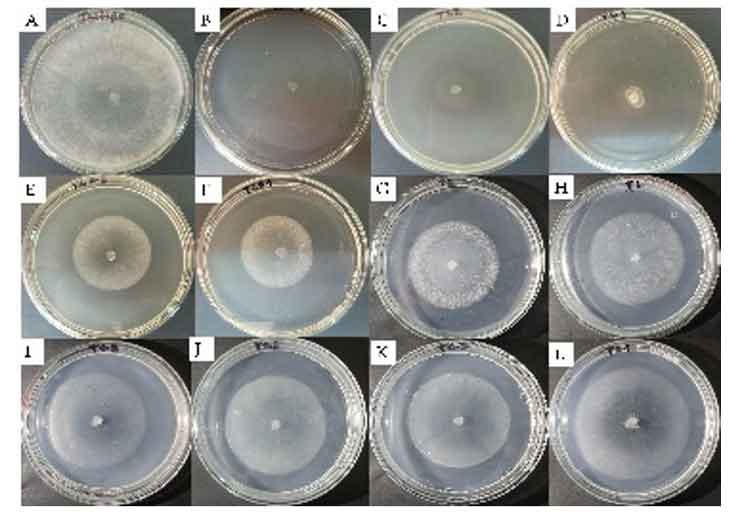

The environment influences the chemical composition of plant essential oil and its biological effect. The purpose of the study was to describe the chemical profile of Tagetes lucida essential oil and to evaluate the in vitro biological effect against B. cinerea. The study was conducted in Texcoco, Mexico in October 2021. Essential oil was obtained from flowering plants by hydrodistillation; the identification of chemical compounds was carried out using the GC-MS technique. The in vitro bioassay employed the method of poisoned agar and mycelium of B. cinerea of three days of growth. Twelve treatments were evaluated: essential oil 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2%, Tween 20 at 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1 and 2%, commercial fungicide, and absolute control (only with sterile double-distilled water). Every 24 h, radial growth of the fungus was measured with a digital vernier and growth rate and inhibition of mycelial growth were estimated. Thirty-one chemical compounds were identified, (1S)-(-)-β-Pinene (36.4%), 1, 3, 5, 7-Cyclooctatetraene (12.7%), eucalyptol (10.6%), and o-Cymene (6.1%). The concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2% inhibited the mycelial growth and sporulation of B. cinerea. The commercial fungicide and the 2% concentration totally inhibited the growth of the fungus. Tween 20 also inhibited mycelial growth. The LC50 was 0.06% and the LC95 was 1.69%. The abundance of terpenes in the essential oil of T. lucida showed a fungicidal effect against B. cinerea. The surfactant had minor effects.

Downloads

References

Acero-Godoy, J.; Guzmán-Hernández, T. y Muñoz-Ruíz, C. 2019. Revisión documental de uso de los aceites esenciales obtenidos de Lippia alba (Verbenaceae), como alternativa antibacteriana y antifúngica. Tecnología en Marcha. 32(1):3-11. Doi.org/10.8845/tm.v32.i1.4114.

Barajas, P. J. S.; Montes-Belmont, R.; Castrejón, F. A.; Flores-Moctezuma, H. E. y Serrato, C. M. A. 2011. Propiedades antifúngicas en especies del género Tagetes. Scientia Fungorum. 3(34):85-91.

Bicchi, C.; Fresia, M.; Rubiolo, P.; Monti, D.; Franz, C. and Goehler, I. 1997. Constituents of Tagetes lucida Cav. ssp. lucida essential oil. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 12(1):47-52. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/%28SICI%291099-1026%28199701%2912%3A1%3C47%3A%3AAID-FFJ610%3E3.0.CO%3B2-7.

Castillo, M. L. E. 2007. Introducción al SAS para Windows. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH). 3ra. Ed. 295 p.

Céspedes C. L.; Avila, J. G.; Martínez, A.; Serrato, B.; Calderón-Mugica, J. C. and Salgado-Garciglia, R. 2006. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of Mexican tarragon (Tagetes lucida). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54(10):3521-3527. Doi.org/10.1021/jf053071w.

Daferera, D. J.; Ziogas, B. N. and Polissiou, M. G. 2000. GC-MS analysis of essential oils from some Greek aromatic plants and their fungitoxicity on Penicillium digitatum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48(6):2576-2581. Doi.org/10.1021/jf990835x.

Dikshit, A. and Husain, A. 1984. Antifungal action of some essential oils against animal pathogens. Fitoterapia LV. 171-176 pp.

Finney, D. J. 1971. Probit analysis. Third edition. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 333 p.

Gómez-López, A.; Aberkane, A.; Petrikkou, E.; Mellado, E.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J. L. and Cuenca-Estrella, M. 2005. Analysis of the influence of concentration, inoculum size, assay medium, and reading time on susceptibility testing of Aspergillus spp. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 43(3):1251-1255. Doi.org/10.1128/jcm.43.3.1251-1255.2005.

Gutiérrez, G. Y.; Scull, L. R.; García, S. G. y Montes, A. A. 2018. Evaluación farmacognóstica, fitoquímica y biológica de un extracto hidroalcohólico de Tagetes lucida Cavanilles. Revista Cubana de Plantas Medicinales. 23(2). https://revplantasmedicinales.sld.cu/index.php/pla/article/view/669/308.

Helal, G. A.; Sarhan, M. M.; Shahla, A. N. K. A. and El-Khair, E. K. A. 2006. Effects of Cymbopogon citratus L. essential oil on the growth, lipid content and morphogenesis of Aspergillus niger ML2-strain. Journal Of Basic Microbiology. 46(6):456-469. Doi.org/10.1002/jobm.200510106.

Inouye, S.; Watanabe, M.; Nishiyama, Y.; Takeo, K.; Akao, M. and Yamaguchi, H. 1998. Antisporulating and respiration-inhibitory effects of essential oils on filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 41(9-10):403-10. Doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00361.x.

Kagezi, G. H.; Kucel, P.; Olal, S.; Pinard, F.; Seruyange, J.; Musoli, P. and Kangire, A. 2015. In vitro inhibitory effect of selected fungicides on mycelial growth of ambrosia fungus associated with the black coffee twig borer, Xylosandrus compactus Eichhoff (Coleoptera: curculionidae) in Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 10(23):2322-2328. Doi.org/10.5897/ajar12.1705. https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJAR/article-full-text/D7529FA53326.

Karalija, E.; Dahija, S.; Tarkowski, P. and Ćavar-Zeljkovic, S. 2022. Influence of climate-related environmental stresses on economically important essential oils of mediterranean Salvia sp. Frontiers in Plant Science. 13:864807. Doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.864807. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.864807/full.

Köppen, W. 1948. Climatología: con un estudio de los climas de la tierra. Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE). México, DF. 479 p. https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/Climatolog%C3%ADa.html?id=kA-IGwAACAAJ&redir-esc=y.

López, L. E.; Peña M. G. O.; Colinas L. M. T.; Diaz, C. F. y Serrato, C. M. A. 2018. Fungistasis del aceite esencial extraído de una población de Tagetes lucida de Hidalgo, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 9(2):329-341. Doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v9i2.1075. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci-arttext&pid=S2007-09342018000200329.

Mwamburi, L. A.; Laing, M. D. and Miller, R. M. 2015. Effect of surfactants and temperature on germination and vegetative growth of Beauveria bassiana. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 46(1):67-74. Doi.org/10.1590/s1517-838246120131077. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4512050/.

Omer, E. A.; Hendawy, S. F.; El-Deen, A. M. N.; Zaki, F. N.; Abd-Elgawad, M. M.; Kandeel, A. M. and Ismail, R.F. 2015. Some biological activities of Tagetes lucida plant cultivated in Egypt. Advances in Environmental Biology. 9(2):82-88. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309111820-Some-biological-activities-of-Tagetes-lucida-plant-cultivated-in-Egypt.

Rammanee, K. and Hongpattarakere, T. 2011. Effects of tropical citrus essential oils on growth, aflatoxin production, and ultrastructure alterations of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 4:1050-1059. Doi.org/10.1007/s11947-010-0507-1. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11947-010-0507-1#citeas.

Rasooli, I.; Rezaei, M. B. and Allameh, A. 2006. Growth inhibition and morphological alterations of Aspergillus niger by essential oils from Thymus eriocalyx and Thymus x-porlock. Food Control. 17(5):359-364. Doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2004.12.002. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0956713505000162.

Regalado, E. L.; Fernández, M. D.; Pino, J. A.; Mendiola, J. and Echemendia, O. A. 2011. Chemical composition and biological properties of the leaf essential oil of Tagetes lucida Cav. from Cuba. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 23(5):63-67. Doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2011.9700485. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10412905.2011.9700485.

Rodríguez, A. M.; Alcaraz, M. L. y Real, C. S. M. 2012. Procedimientos para la extracción de aceites esenciales en plantas aromáticas. SAGARPA-CONACYT. México, DF. 47 p.

SAS Institute Inc. 2023. SAS® OnDemand for Academics. https://www.sas.com/es-mx/software/on-demand-for-academics.html.

Serrato, C. M. A. 2014. El recurso genético cempoalxóchitl (Tagetes spp.) de México (Diagnóstico). México, DF. 185 p.

Sinclair, C. G. and Cantero, D. 1989. Fermentation modelling. In: fermentation a practical approach. McNeil, B. L. and Harvey, M. (Eds.). IRL Press, New York. 65-112 pp. https://cienciasagricolas.inifap.gob.mx/index.php/agricolas/article/view/2077/3209.

Soylu, E. M.; Kurt, Ş. and Soylu, S. 2010. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the essential oils of various plants against tomato grey mould disease agent Botrytis cinerea. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 143(3):183-189. Doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.08.015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168160510004757.

Tančinová, D.; Mašková, Z.; Mendelová, A.; Foltinová, D.; Barboráková, Z. and Medo, J. 2022. Antifungal activities of essential oils in vapor phase against Botrytis cinerea and their potential to control postharvest strawberry gray mold. Foods. 11(19):2945. Doi.org/10.3390/foods11192945. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/19/2945.

Torres-Martínez, R.; Moreno-León, A.; García-Rodríguez, Y. M.; Hernández-Delgado, T.; Delgado-Lamas, G. and Espinosa-García, F. J. 2022. Tagetes lucida Cav. essential oil and the mixture of its main compounds are antibacterial and modulate antibiotic resistance in multi-resistant pathogenic bacteria. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 75(2):210-223. Doi.org/10.1111/lam.1372. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35419861/.

Toju, H.; Tanabe, A. S.; Yamamoto, S. and Sato, H. 2012. High-Coverage ITS primers for the DNA-Based identification of Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes in environmental samples. Plos One. 7(7):1-11. Doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040863. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0040863.

Turner, B. L. 1996. The comps of Mexico: A systematic account of the family Asteraceae, vol. 6. Tageteae and Anthemideae. Phytologia Memoirs. Texensis Publishing. Gruver, Texas, USA. 93 p. https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/The-Comps-of-Mexico-Tageteae-and-Anthemi.html?id=6gZHAAAAYAAJ&redir-esc=y.

Valkovszki, N. J.; Szalóki, T.; Székely, Á.; Kun, Á.; Kolozsvári, I.; Zima, I. S.; Tavaszi-Sárosi, S. and Jancsó, M. 2023. Influence of soil types on the morphology, yield, and essential oil composition of common sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Horticulturae. 9(9):1037. Doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9091037. https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/9/9/1037.

Zarate-Escobedo, J.; Castañeda-González, E. L.; Cuevas-Sánchez, J. A.; Carrillo-Fonseca, C. L.; Ortiz-Torres, C.; Ibarra-Estrada, E. y Serrato-Cruz, M. A. 2018. Aceite esencial de algunas poblaciones de Tagetes lucida Cav. de las regiones norte y sur del Estado de México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana. 41(2):199-209. Doi.org/10.35196/rfm.2018.2.199-209. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci-arttext&pid=S0187-73802018000200199.

Zhao, J.; Quinto, M.; Zakia, F. and Li, D. 2023. Microextraction of essential oils: a review. Journal of Chromatography A. 1708:464357. Doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464357. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0021967323005824.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.