Late pruning: an alternative for adapting viticulture to climate change?

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v14i8.3167Keywords:

Vitis vinifera, climate change, imbalance, phenology, pruning, ripeness, temperatureAbstract

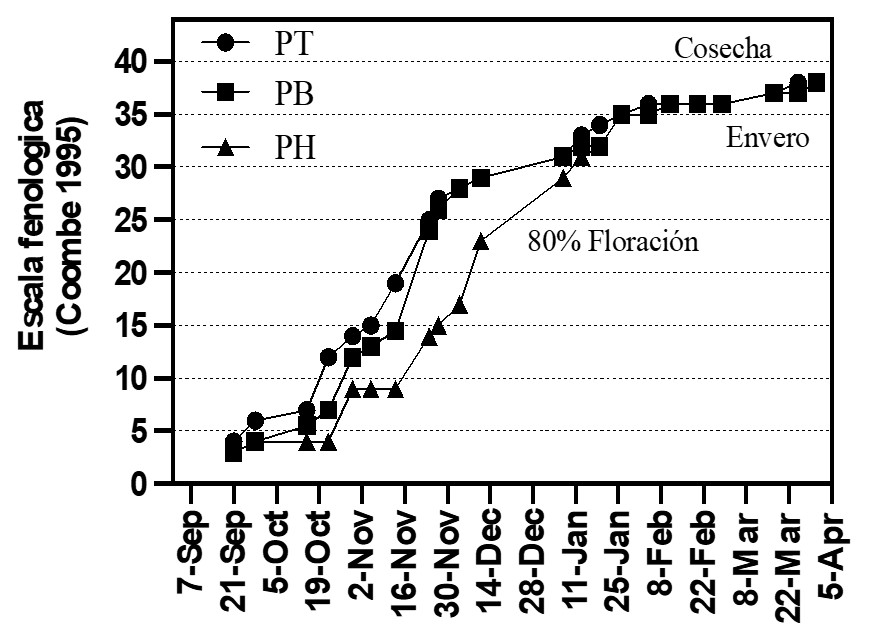

The quality and production of the vine depend on the climate; therefore, changes in it can affect its sustainability. For Chile, an increase of at least 1 °C in temperatures in the Central Valley has been projected, which can directly affect the ripening process of vines, accelerating the accumulation of sugars, affecting organic acids, and decreasing phenolic compounds, which translates into an imbalance of ripening. Considering this, to ensure the sustainability of viticulture in the face of climate change, management alternatives that allow optimal ripening in the face of changing climatic conditions are sought. One of these alternatives is late pruning. Late pruning proposes to delay the pruning dates after bud break and before flowering, eliminating the reserves already mobilized in the plant, thus generating a phenological delay. This delay in growth would allow for less accelerated ripening. To assess the effectiveness of this technique, three pruning dates: traditional pruning (TP), pruning at bud break (BP), and pruning in 2-3 leaves (LP), were evaluated in a commercial vineyard of the cv Cabernet Sauvignon in the Central Valley during the 2020-2021 season. The preliminary results of this study show positive expectations of this technique, delaying the phenology of the crop and the harvest dates. However, this seems to depend on the phenological moment where late pruning is performed and the varietal characteristics. The BP presented a delay of the harvest time of six days without affecting the production or the initial quality of the berries. Likewise, the LP affected the set of bunches and did not delay the harvest. The results showed that it is possible to delay harvest dates; nevertheless, it is relevant to consider other variables such as variety, phenological moment, soil, and climate.

Downloads

References

Banfi, S. P. 2017. Antecedentes de los mercados del vino y de la uva vinífera julio de 2017. Chile. Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias (ODEPA). 1-18 pp.

Bustos, M.; Prieto, J.; Fanzone, M.; Sari, S. y Pérez, J. 2019. La poda tardía podría mitigar el daño de las altas temperaturas en la calidad del vino. Campo Andino. 50:26-27.

Bock, A.; Sparks, T.; Estrella, N. and Menzel, A. 2013. Climate induced changes in grapevine yield and must sugar content in Franconia, Germany between 1805 and 2010. PLOS ONE. 8(7):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069015

CEPAL. 2012. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. La economía del cambio climático en Chile. CEPAL. 134 p.

Concha, V. C. 2015. Efecto de distintas fechas de poda sobre la brotación y tiempo a envero en vides de cabernet Sauvignon. Memoria de Título. Escuela de Pregrado, Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas-Universidad de Chile. 33 p.

Coombe, B. G. 1995. Growth stages of the grapevine: adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 1(2):104-110. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.1995.tb00086.x

Hamman, R.; Renquist, A. R. and Huges, H. G. 1990. Pruning effects on cold hardiness and water content during deacclimation of merlot bud and cane Tissues. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 41(3):251-260.

Poni, S.; Sabbatini, P. y Palliotti, A. 2022. Facing spring frost damage in grapevine: recent developments and the role of delayed winter pruning a review. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 73(4):211-249. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.2022.22011.

Sadras, V. 2016. Decompressing harvest and preserving wine identity. Final report to Australian grape and wine authority. SARDI Plant Research Center. 1-36 pp.

Salazar-Parra, C.; Aguirreolea, J.; Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Irigoyen, J. J. y Morales, F. 2010. Effects of climate change scenarios on tempranillo grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) ripening: response to a combination of elevated CO2 and temperature, and moderate drought. Plant and Soil. 337:179-191. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0514-z

Van Leeuwen, C. and Darriet, P. 2016. The impact of climate change on viticulture and wine quality. J. Wine Econ. 11(1):150-167. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jwe.2015.21

Vicuña, S.; Bustos, E.; Cabrra, C.; Cifuentes, L.; Valdés, J. M. y Gironas, J. 2017. Cambio climático en la región Metropolitana de Santiago. En estrategia de resiliencia gobierno metropolitano de Santiago. Santiago. Centro UC cambio global y GreenLabUC. 74 p.

Yamane, T.; Jeong, S. T.; Goto, Y. N.; Koshita, Y. and Kobayashi, S. 2006. Effects of temperature on Anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berry skins. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 57(1):54-59. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.2006.57.1.54.

Zheng, W.; García, J.; Balda, P. and Martínez, T. F. 2017. Effects of late winter pruning at different phenological stages on vine yield components and berry composition in La Rioja, North-central Spain. OENO One. 51(4):363-372. https://doi.org/ 10.20870/oeno-one.2017.51.4.1863. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20870/oeno-one.2017.51.4.1863

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.