Cost-benefit of a protected cultivation system of tomato in San Quintín

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v14i5.3063Keywords:

protected crop, tomato, San QuintinAbstract

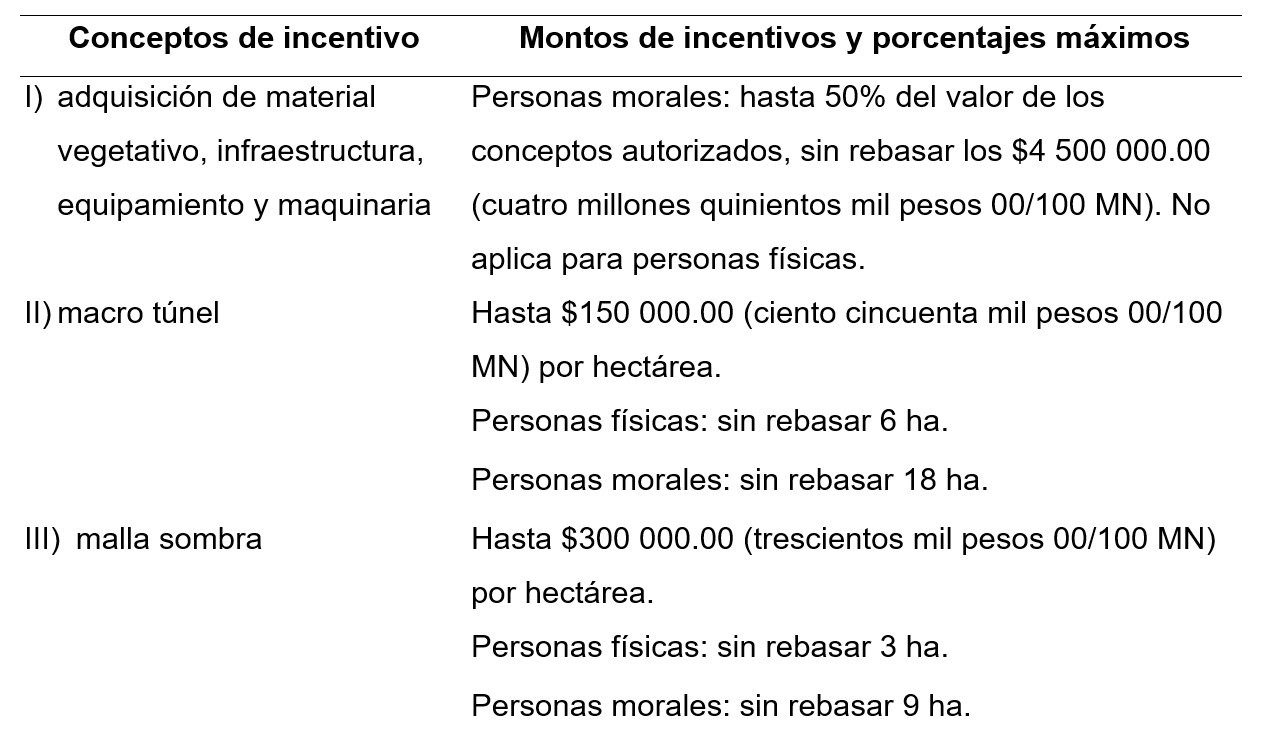

This paper explains the benefits of implementing a protected cultivation system for farmers in the San Quintín Valley (Baja California, Mexico) engaged in the production of vegetables, particularly tomatoes. The importance of carrying out this research lies in the fact that the implementation of a protected cultivation system (greenhouse-shade mesh) increases production and improves the quality of tomato crops, while generating an important technological advance for the agricultural sector, allowing the obtaining of benefits for both: the farmer and the industry. The ideal sources of financing to carry out the system of this type of cultivation are also part of this writing. To this end, a methodology that involved the following two steps was developed: collection of theoretical information and data collection through a questionnaire applied to eight tomato-producing companies in the San Quintín Valley in 2020. The results infer that the majority opt for cultivation with shade mesh for the production of the products, but that in turn it is very difficult to obtain government resources. It is concluded that the shade mesh is the type of protected cultivation system with greater use, through which production can be increased and the quality of products can be improved, there are still limitations in the acquisition of government support, and it is for that reason that most use the capital of their company and the financing of a bank for its implementation.

Downloads

References

Armendariz-Erives, S. 2007. Desafíos y riesgos agrícolas ante el calentamiento global. Oportunidades y retos de la ingeniería agrícola ante la globalización y el cambio climático. UACH-URUZA. 1ra. Ed. México. 73-79 pp.

Castilla, N. 2007. Invernaderos de plástico. Tecnología y manejo. Mundi Prensa. 25va Ed. México, DF. 63-94 pp.

Cih-Dzul, I. R.; Jaramillo-Villanueva, J. L.; Tornero-Campante, M. A. y Schwentesius-Rindermann, R. 2011. Caracterización de los sistemas de producción de tomate (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) en el estado de Jalisco, México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosy. 14(2):501-512.

Criollo, E. V. y Limones, G. A. 2018. Análisis de los factores que inciden en los procesos de internacionalización de las MIPYMES de frutas y hortalizas no tradicionales. Tesis de licenciatura. Universidad de Guayaquil, Ecuador. 30-34 pp.

FIRA. 2019. Fideicomisos Instituidos en Relación con la Agricultura. Panorama agroalimentario. Tomate Rojo. FIRA. México, DF.

INEGI. 2020. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. Panorama sociodemográfico de México. México, DF. 61-79 pp.

Lezama, E. 2018. Análisis de las problemáticas de gestión el agua en la ciudad de ensenada, Baja California: hacia un cambio de paradigma en la gestión del agua. Tesis de maestría. Colegio de la Frontera Norte: Tijuana. 13-45 pp.

López, P. J.; Montoya, R. B.; Brindis, R. C.; Sánchez, M. M. A. L.; Cruz. C. E. y Morales, R. B. 2011. Estructuras utilizadas en la agricultura protegida. Rev. Fuente. 3(8):21-27.

Lugo-Sánchez, M. Á.; Flores-Canales, R. J.; Isiordia-Aquino, N.; Lugo-García, G. A. y Reyes-Olivas, Á. 2019. Ácaros fitófagos asociados a jitomate en el norte de Sinaloa, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 10(7):1541-1550.

Moreno, A.; Aguilar, J. y Luévano, A. 2011. Características de la agricultura protegida y su entorno en México. Rev. Mex. Agron. 29(1):763-774.

Ortega-Martínez, L. D.; Ocampo-Mendoza, J.; Sandoval-Castro, E.; Martínez-Valenzuela, C.; Huerta-De la Peña, A. y Jaramillo-Villanueva, J. L. 2014. Caracterización y funcionalidad de invernaderos en Chignahuapan Puebla, México. Rev. Bio Ciencias. 2(4):261-270.

Ramírez-Vargas. C. 2019. Extracción de nutrientes, crecimiento y producción del cultivo de pepino bajo sistemas de cultivo protegido. Rev. Tecnología en Marcha. 32(1):107-117.

Ro, S.; Chea, L.; Ngoun, Z. P.; Stewart, Z. P.; Roeurn, S.; Theam, P.; Lim, S.; Sor, R.; Kosal, M.; Roeun, M.; Dy, K. S. and Vara, P. V. 2021. Response of tomato genotypes under different high temperatures in field and greenhouse conditions. Plants. 10(3):449-450.

SAGARPA. 2019. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación. Informe tercer trimestre. SAGARPA. México. 21-29 pp.

Santos, B. M.; Obregón, O. H. A. y Salamé, D. T. P. 2010. Producción de hortalizas en ambientes protegidos: estructuras para la agricultura protegida. EDIS. 1(6):1-5.

Saynes, V.; Etchevers, J. D.; Paz, R. y Alvarado, L. O. 2016. Emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en sistemas agrícolas de México. Terra Latinoam. 34(1):83-96.

SCYSA. 2020. Secretaría del Campo y la Seguridad Alimentaria. Padrón de productores y productos alimenticios de Baja California. 5-13 pp.

SEFOA. 2015. Secretaría de Fomento Agropecuario. Panorama general de ‘zona San Quintín’ Baja California. México. 56-81 pp.

SIAP. 2022. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Expectativas agroalimentarias agosto. México, DF.

Soto, A. R.; Vargas, R. A. y Jiménez, B. J. 2020. Ecosistema de datos agrícolas: sector hortícola mexicano. Repositorio internacional de investigadores en competitividad. 14(14):1-21.

Wittwer, S. H. y Castilla, N. 1995. Protected cultivation of horticultural crops worldwide. Hort. Technol. 5(1):6-23.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.