Polyphenols from different plant sources and their in vitro effect against chickpea pathogens

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v12i8.2742Keywords:

Fusarium, Macrophomina, polyphenolsAbstract

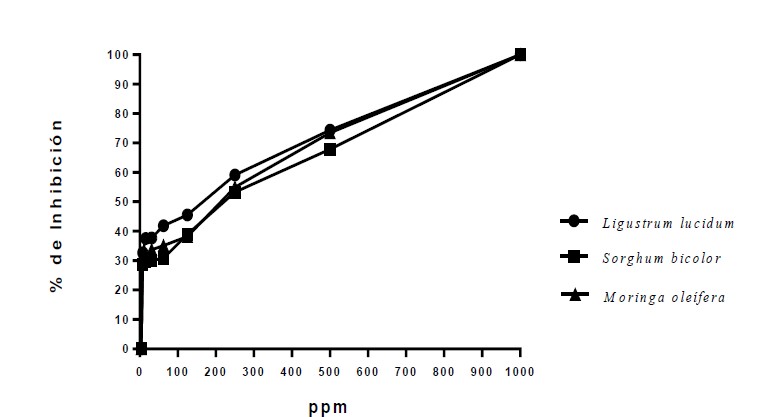

The production of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is constantly compromised by a complex of pathogens that cause root wilt and rot (RWR). Some of the strategies used for the management of this disease are the use of resistant varieties, crop rotation, solarization, removal of regrowths and use of seeds free of pathogens or treated with fungicides, although the results have been limited or not very satisfactory, in recent years, biological control and organic products have become more important. In the present work, polyphenols were obtained from ethanolic extracts by the ultrasound-microwave-assisted technique of plant species: thunder (L. lucidum) leaf, sorghum (S. bicolor) grains and moringa (M. oleifera) leaves. The corresponding qualitative analysis was carried out using HPLC masses and the antifungal effect of each group of polyphenol extracts on three phytopathogenic fungi that make up the complex of root wilt and rot was determined by means of the technique of plate dilution and poisoned medium. The percentage of inhibition and the inhibitory concentration (IC50) were determined. The results indicate that polyphenols have high biological effectiveness on the fungus Macrophomina and Fusarium solani, the activity for Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris depended on the polyphenols of each plant species; polyphenols of L. lucidum with a concentration of 491.99 ppm. Additionally, it was found that all the groups of polyphenols had in their chemical composition some compounds of recognized microbial activity such as: flavones, anthocyanins, catechins and alkylphenols, among others.

Downloads

References

Arif, M.; Chawla, S.; Zaidi, M. W.; Rayar, J. K.; Variar, M. y Singh. 2012. Desarrollo de cebadores específicos para los géneros Fusarium y F. solani utilizando la subunidad de ADNr y el gen del factor de elongación de la transcripción (TEF-1α). Rev. Afric. Biotecn. 11(2):444-447. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230555127.

Arvayo, O. R. M.; Esqueda, M.; Acedo F. E.; Sánchez, A. and Gutiérrez, A. 2011. Morphological variability and races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris associated with chickpea (Cicer arietinum) crops. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 6(1):114-121. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/280020049. Ascacio, V. J. A.; Aguilera, C. A. F.; Buenrostro, J. J.; Prado, B. A.; Rodríguez, H. R. and Aguilar, C. N. 2016. The complete biodegradation pathway of ellagitannins by Aspergillus niger in solid‐state fermentation. J. Basic Microbiol. 56(4):329-336. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500557. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201500557

Babu, B. K.; Saxena, A. K.; Srivastava, A. K. and Arora, D. K. 2007. Identification and detection of Macrophomina phaseolina by using species-specific oligonucleotide primers and probe. Mycologia. 99(6):797-803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15572536.2007.11832511. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15572536.2007.11832511

Basco, M. J.; Bisen, K.; Keswani, C. and Singh, H. B. 2017. Biological management of Fusarium wilt of tomato using biofortified vermicompost. Mycosphere. 8(3):467-483. http://dx.doi.org/10.5943/mycosphere/8/3/8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5943/mycosphere/8/3/8

Chandra, S.; Choure, K.; Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. 2007. Rhizosphere competent Mesorhizobiumloti MP6 induces root hair curling, inhibits Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and enhances growth of Indian mustard (Brassica campestris). Brazilian J. Microbiol. 38(2):124-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822007000100026. De-Asmundis, C.; Romero, C. H.; Acevedo, H. A.; Pellerano, R. G. y Vázquez, F. A. 2011. Funcionalización de una resina de intercambio ionico para la preconcentracion de HG (II). Avances en Ciencias e Ingeniería. 2(1):63-70. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id= 323627681006. Duarte, Y.; Pino, O. y Martínez, B. 2013. Efecto de cuatro aceites esenciales sobre Fusarium spp. Rev. Protec. Veget. 28(3):232-235. http://scielo.sld:cu/scielo.php?script=sci-arttext&pid= S=1010-27522013000300013. Dwivedi, S. K. 2015. Eficacy of some medical plant extract against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causing chickpen wilt. Asian J. Crop Sci. 7(2):138-146. doi:10.3923/ajcs.2015. 138.146.

Gabrielson, J.; Hart, M.; Jarelöv, A.; Kühn, I.; McKenzie, D. and Möllby, R. 2002. Evaluation of redox indicators and the use of digital scanners and spectrophotometer for quantification of microbial growth in microplates. J. Microbiol. Methods. 50(1):63-73. http//dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00011-8. Gakuya, D. W.; Itoga, S. M.; Mbaria, J. M.; Muthee, J. K. and Musau, J. K. 2013. Ethnobotanical survey of biopesticides and other medicinal plants traditionally used in meru central district of Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 145(2):547-553. Doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.028

Jasso-Rodríguez, D.; García, R. R.; Castillo, H. F.; González, C. A.; Galindo, A. S.; Quintanilla, J. V. and Zuccolotto, L. M. 2011. In vitro antifungal activity of extracts of Mexican Chihuahuan desert plants against postharvest fruit fungi. Industrial Crops and Products. 34(1):960-966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.03.001. Jiménez, G. M. M.; Pérez, A. E. and Jiménez, D. R. M. 2001. Identification of pathogenic races 0, 1B/C, 5, and 6 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris with random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107(2):237‐248. doi: 10.1023/a: 1011294204630. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.03.001

Landa, B. B.; Navas, C. J. A.; Jiménez, G. M. M.; Katan, J.; Retig, B. and Jiménez D. R. M. 2006. Temperature response of chickpea cultivars to races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris, causal agent of Fusarium wilt. Plant Dis. 90(3):365‐374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/PD-90-0365. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1094/PD-90-0365

Masoko, P.; Picard, J. and Eloff, J. N. 2005. Antifungal activities of six South African Terminalia species (Combretaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 99(2):301-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jep.2005.01.061. Matsuura, H. N. and Fett, N. A. G. 2017. Plant alkaloids: main features, toxicity, and mechanisms of action. Plant toxins Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Carlini, C. R. and Igabue, B. R. (Ed.). 243-261p. doi 10.1007/978-94-007-6728-7-2-1, 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.061

Morales, G. J. A. y Durón, N. L. J. 2004. Aspectos generales. Morales, G. J. A.; Durón, N. L. J.; Martínez, D. G.; Núñez, M. D. J. H. y Fu, C. A. A. (Ed.). El cultivo de garbanzo blanco en Sonora. Libro Técnico núm. 6. INIFAP-Campo Experimental Costa de Hermosillo, Sonora, México. 11-24 pp.

Moreno, L. S.; González, S. L. N.; Salcedo, M. S. M.; Cárdenas, Á. M. L. y Perales, R. A. 2011. Efecto antifúngico de extractos de gobernadora (Larrea tridentata L.) sobre la inhibición in vitro de Aspergillus flavus y Penicillium sp. Polibotánica. 32:193-205. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62119933012. Navas, C. J. A.; Hau, B. and Jiménez‐Díaz, R. M. 1998. Effect of sowing date, host cultivar, and race of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris on development of Fusarium wilt of chickpea. Phytopathology. 88(12):1338‐1346. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.12.1338

Paredes, E. J. E.; Carrillo, F. J. A.; García, E. R. S.; Allende, M. R.; Sañudo, B. J. A. y Valdez, T. J. B. 2009. Microorganismos antagonistas para el control del complejo de hongos causantes de la rabia del garbanzo (Cicer arietinum L.) en el Estado de Sinaloa, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopat. 27(1):27-35. Sharma, K. D. and Muehlbauer, F. J. 2007. Fusarium wilt of chickpea: physiological specialization, genetics of resistence and resistence gene tagging. Euphytica. 157(1):1-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10681-007-9401-y. Sparks, T. C.; Hahn, D. R. and Garizi, N.V. 2017. Natural products, their derivatives, mimics and synthetic equivalents: role in agrochemical discovery. Pest Manag. Sci. 73(4):700-715. Doi: 10.1002/ps.4458. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.4458

Sánchez, S. M.; Gambardella, J. L. and Enriquez, I. D. 2013. First report of crown rot of strawberry caused by Macrophomina phaseolina in Chile. Plant Dis. 97-996 p. http://dx.doi.org /10.1094/PDIS-12-12-1121-PDN. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-12-12-1121-PDN

SIAP. 2017. Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Avance de siembras y cosechas, resumen nacional por cultivo. https://www.gob.mx/siap/.

Toma, M.; Vinatoru, M.; Paniwnyk, L. and Mason, T. 2001. Investigation of the effects of ultrasound on vegetals tissues during solvent extraction. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 8(2):137-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4177 (00)00033-X. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4177(00)00033-X

Yossen, V. E. y Conles, M. Y. 2016. Eficacia de fungicidas in vitro para el control de Fusarium oxysporum y F. proliferatum, agentes causales de marchitamiento en el cultivo de orégano en la Argentina. Rev. Industrial y Agrícola de Tucumán. 91(1):19-25. https://riat.eeaoc. org.ar/ojs/ index.php /riat/ article/view/v91n1a03/33.

Zacarés, L. 2008. Nuevas aportaciones al metabolismo secundario del tomate, identificación y estudio de moléculas implicadas en la respuesta a la infección con Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. https://doi.org/10.4995/ Thesis/10251/3021, es.

Zaker, M. 2014. Antifungal evaluation of some plant extracts in controlling Fusarium solani, the causal agent of potato dry rot in vitro and in vivo. Inter. J. Agri. Biosci. 3(4):190-195. www.ijagbio.com.

Zhang, J. Q.; Zhu, Z. D.; Duan, Z. D.; Wang, C. X. and Li, H. J. 2011. First report of charcoal rot caused by Macrophomina phaseolina on mungbean in china. Plant Dis. 95(7):95-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-01-11-0010. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-01-11-0010

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.