Detection of the xyl3 gene in strains of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v14i6.2711Keywords:

mutations, positive selection, xylanase geneAbstract

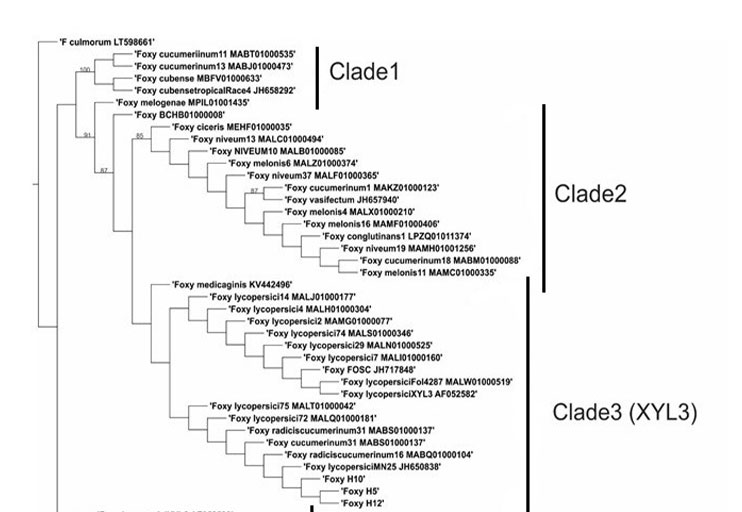

The mechanisms of Fusarium oxysporum related to the degradation of structural components of the root, such as xylan, are very important since the colonization of this organ is a key piece in the establishment of the disease. The present study focused on detecting the gene coding for the xylanase xyl3 enzyme in strains of F. oxysporum f. sp. vanillae and searching for homologues to this gene in sequences of other formae speciales and species of the Fusarium genus, in order to determine the phylogenetic relationships between xylanases within the F. oxysporum species complex, as well as to search for evidence of natural selection. The results indicated that, of the nine strains evaluated, only three had a copy of the xyl3 gene. The phylogeny showed eight clades, where clade 3 was consistent with the classification of xyl3, while the other types of xylanases were grouped in clade 2. The natural selection test showed no evidence of positive selection within the phylogeny, suggesting that the neutral mutation is responsible for the diversity in the xylanase gene among the F. oxysporum species complex, leading to the proposal that the gene does not appear to have changed with colonization of new hosts.

Downloads

References

Abdul-Karim, N. F.; Mohd, M.; Izham-Mohd, N. M and Zakaria, L. 2016. Saprophytic and potentially pathogenic Fusarium species from peat soil in Perak and Pahang. Trop Life Sci. Res. 27(1):1-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4807956/.

Adame-García, J.; Trigos, Á.; Iglesias-Andreu, L. G.; Flores-Estévez, N. and Luna-Rodríguez, M. 2011. Isozymic and pathogenic variations of Fusarium spp. associated with vanilla stem and root rotting. Trop subtrop agroecosystems. 13(3):299-306. https://www.revista.ccba.uady.mx/ojs/index.php/TSA/article/view/1330/663.

Adame-García, J.; Rodriguez-Guerra, R.; Iglesias-Andreu, L. G.; Ramos-Prado, J. M. and Luna-Rodríguez, M. 2015. Molecular identification and pathogenic variation of Fusarium species isolated from Vanilla planifolia in Papantla Mexico. Bot. Sci. 93(3):669-678. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.142. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.142

Adame-García, J.; Flores-Rosa, F. R.; Ricaño-Rodríguez, J. and Luna-Rodríguez, M. 2016. Adequacy of a protocol for amplification of EF-1α gene of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae. ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 11(6):236-241. http://www.arpnjournals.org/jabs/ research-papers/rp-2016/jabs-0616-804.pdf.

Demers, J. E.; Gugino, B. K. and Jiménez-Gasco, M. M. 2015. Highly diverse endophytic and soil Fusarium oxysporum populations associated with field-grown tomato plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81(1):81-90. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02590-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02590-14

De-Vries, R. P. and Visser J. 2001. Aspergillus enzymes involved in degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Microbiol Mol. Biol Rev. 65(4):497-522. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.65.4.497-522.2001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.65.4.497-522.2001

Edel-Hermann, V. and Lecomte, C. 2019. Current status of Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales and races. Phytopathology. 109(4):512-530. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0320-RVW.

Flores-Rosa, F. R.; Luna, E.; Adame-García, J.; Iglesias-Andreu, L. G. and Luna-Rodríguez, M. 2018. Phylogenetic position and nucleotide diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae worldwide based on translation elongation factor 1α sequences. Plant Pathol. 67(6):1278-1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12847. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12847

Goloboff, P. A.; Farris, J. S. and Nixon, K. C. 2008. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics. 24(5):774-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00217.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00217.x

González-Oviedo, N.; Iglesias-Andreu, L. G.; Flores-Rosa, F. R.; Rivera-Fernández, A. and Luna-Rodríguez M. 2022. Genetic analysis of the fungicide resistance in Fusarium oxysporum associated to Vanilla planifolia. Mex. J. Phytopathol. 40(3):1-19. https://doi.org/10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.2203-3.

Gómez-Gómez, E.; Ruíz-Roldán, M. C.; Pietro, A.; Roncero, M. I. G. and Hera, C. 2002. Role in pathogenesis of two endo-β-1,4-xylanase genes from the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Fungal Genet Biol. 35(3):213-222. https://doi.org/10.1006/ fgbi.2001.1318. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/fgbi.2001.1318

Gurjar, G.; Barve, M.; Giri, A. and Gupta, V. 2009. Identification of Indian pathogenic races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris with gene specific, ITS and random markers. Mycologia. 101(4):484-495. https://doi.org/10.3852/08-085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3852/08-085

Hall, T A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 41:95-98.

Hughes, A. L. and Friedman, R. 2008. Codon-based tests of positive selection, branch lengths, and the evolution of mammalian immune system genes. Immunogenetics. 60:495-506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-008-0304-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-008-0304-4

Jorge, I.; Rosa, O.; Navas-Cortés, J. A.; Jiménez-Díaz, R. M and Tena, M. 2005. Extracellular xylanases from two pathogenic races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris: enzyme production in culture and purification and characterization of a major isoform as an alkaline endo beta xylanase of low molecular weight. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 88:48-59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-004-7584-y. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-004-7584-y

Kalluri, U. C.; Yin, H.; Yang, X. and Davison, B. H. 2014. Systems and synthetic biology approaches to alter plant cell walls and reduce biomass recalcitrance. Plant Biotechnol J. 12(9):1207-1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12283. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12283

Koyyappurath, S.; Conéjéro, G.; Dijoux, J. B.; Lapeyre-Montès, F.; Jade, K.; Chiroleu, F.; Gatineau, F.; Verdeil, J. L.; Besse, P. and Grisoni, M. 2015. Differential responses of vanilla accessions to root rot and colonization by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-vanillae. Front Plant Sci. 6:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.01125. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.01125

Koyyappurath, S.; Atuahiva, T.; Le Guen, R.; Batina, H.; Le Squin, S.; Gautheron, N.; Edel-Hermann, V.; Peribe, J.; Jahiel, M.; Steinberg, C.; Liew, E. C. Y.; Alabouvette, C.; Besse, P.; Dron, M.; Sache, I.; Laval, V. and Grisoni, M. 2016. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-vanillae is the causal agent of root and stem rot of vanilla. Plant Pathol. 65(4):612-625. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12445. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12445

Kumar, S.; Stecher, G. and Tamura, K. 2016. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33(7):1870-1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

Laurence, M. H.; Summerell, B. A. and Liew, E. C. Y. 2015. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. canariensis: evidence for horizontal gene transfer of putative pathogenicity genes. Plant Pathol. 64(5):1068-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12350. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12350

Metzger, K. J. and Thomas, M. A. 2010. Evidence of positive selection at codon sites localized in extracellular domains of mammalian CC motif chemokine receptor proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 10(139):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-10-139. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-10-139

Nei, M. and Gojobori, T. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3(5):418-426. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410

O’Donnell, K.; Gueidan, C.; Sink, S.; Johnston, P. R.; Crous, P. W.; Glenn, A.; Riley, R.; Zitomer, N. C.; Colyer, P. and Waalwijk, C. 2009. A two-locus DNA sequence database for typing plant and human pathogens within the Fusarium oxysporum species complex. Fungal Gen. Biol. 46(12):936-948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.006

Olivain, C.; Humbert, C.; Nahalkova, J.; Fatehi, J.; L’Haridon, F. and Alabouvette, C. 2006. Colonization of tomato root by pathogenic and nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum strains inoculated together and separately into the soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72(2):1523-1531. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.2.1523-1531.2006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.2.1523-1531.2006

Pattathil, S.; Hahn, M. G.; Dale, B. E. and Chundawat, S. P. S. 2015. Insights into plant cell wall structure, architecture, and integrity using glycome profiling of native and AFEXTM-pretreated biomass. J. Exp. Bot. 66(14):4279-4294. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ erv107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv107

Peña, M. J.; Kulkarni, A. R.; Backe, J. Boyd, M. O.; Neill, M. A. and York, W. S. 2016. Structural diversity of xylans in the cell walls of monocots. Planta. 244:589-606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-016-2527-1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-016-2527-1

Pinaria, A. G.; Liew, E. C. Y. and Burgess, L. W. 2010. Fusarium species associated with vanilla stem rot in Indonesia. Australasian Plant. Pathol. 39:176-183. https://doi.org/10.1071/AP09079. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1071/AP09079

Pinaria, A. G.; Laurence, M. H.; Burgess, L. W. and Liew, E. C. Y. 2015. Phylogeny and origin of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vanillae in indonesia. Plant Pathol. 64(6):1358-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12365. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12365

Ruiz-Roldan, M. C.; Di-Pietro, A.; Huertas-Gonzalez, M. D. and Roncero, M. I. 1999. Two xylanase genes of the vascular wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum are differentially expressed during infection of tomato plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:530-536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004380050997. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s004380050997

Soto-Arenas, M. A y Solano-Gómez, A. R. 2007. Ficha técnica de Vanilla planifolia. En: información actualizada sobre las especies de orquídeas del PROY-NOM-059-ECOL-2000. Instituto Chinoin A.C. Herbario de la Asociación Mexicana de Orquideología AC. Proyecto No. W029. México. DF. 1-18 pp. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/conocimiento/ ise/fichasnom/Vanillaplanifolia00.pdf.

Turrà, D.; Ghalid, M.; Rossi, F. and Pietro, A. 2015. Fungal pathogen uses sex pheromone receptor for chemotropic sensing of host plant signals. Nature. 527:521-524. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15516. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15516

Waweru, B.; Turoop, L.; Kahangi, E.; Coyne, D. and Dubois, T. 2014. Non-pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum endophytes provide field control of nematodes, improving yield of banana (Musa sp.). Biological Control. 74:82-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol. 2014.04.002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.04.002

Zhang, J.; Nielsen, R.; and Yang, Z. 2005. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22(12):2472-2479. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi237. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi237

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.