Characterization of wild and cultivated chia populations

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v12i7.2243Keywords:

cultivated, dendrogram, principal components, Salvia, wild chiaAbstract

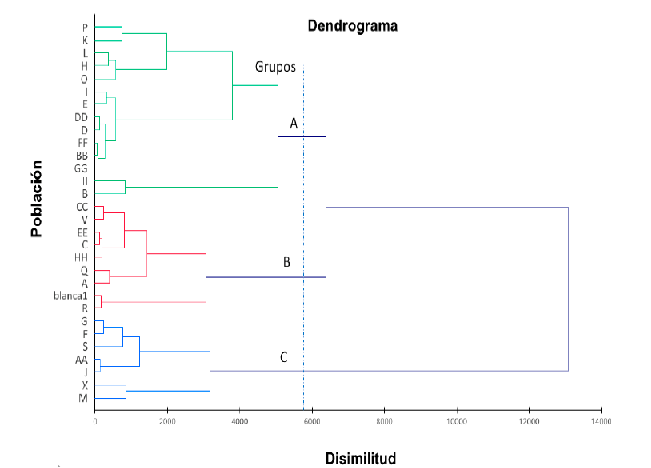

It is an annual crop of temperate and semi-warm environments with clay and sandy soils. There are wild populations in Mexico that in pre-Columbian times allowed the selection of plants with larger fruit that did not disperse the seed. Domesticated varieties, compared to wild ones, have larger seeds, more compact inflorescence, closed calyces, longer flower, apical dominance, uniformity in flowering and ripening periods. Chia contains between 9 and 23% protein, 26-41% carbohydrates and 30 to 33% oil, 40% dietary fiber and calcium and a high antioxidant content. It has acquired great importance because it is considered a functional food. There is consensus on the importance of the study and conservation of plant genetic resources. The objective of this research was to characterize the morphological diversity of 31 chia genotypes based on the variations identified between wild and domesticated populations. It was observed that the presence of anthocyanins is characteristic of wild plants, as well as the presence of open calyx, which is related to the dispersal of the seeds; these were smaller and darker, and their calyces were short and opened when ripe. The size of the seed and the weight of a thousand seeds are highly correlated with the yield per plant. Domesticated plants presented closed calyx, without anthocyanin coloration, reduction of pubescence in most of the plant, larger inflorescence, greater number of florets, greater seed weight, higher yield. Domesticated, semi-domesticated and wild populations were characterized and grouped. The wild ones have an open calyx. The semi-domesticated ones are similar to the cultivated ones but have an open calyx. The domesticated ones had apical dominance, greater size of spike and closed calyx.

Downloads

References

Ayerza, R. and Coates, W. 2004. Composition of chia (Salvia hispanica) grown in six tropical and subtropical ecosystems of South America. Tropical Sci. 44(3):131-135. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ts.154.

Baginsky, C.; Arenas, J.; Escobar, H.; Garrido, M.; Valero, N.; Tello, D. and Silva, H. 2016. Growth and yield of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) in the mediterranean and desert climates of chile. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 76(3):255-264. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-58392016000 300001.

Cahill, J. P. 2004. Genetic diversity among varieties of chia (Salvia hispanica L.). Genetic resources and crop evolution. 51(7):773-781. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GRES.00000 34583.20407.80.

Cahill, J. P. 2005. Human selection and domestication of chia (Salvia hispanica L.). J. Ethnobiol. 25(2):155-174. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771.

Cahill, J. P. and Ehdaie, B. 2005. Variation and heritability of seed mass in chia (Salvia hispanica L.). Genetic resources and crop evolution. 52(2):201-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-003-5122-9.

Cahill, J. P. and Provance, M. C. 2002. Genetics of qualitative traits in domesticated chia (Salvia hispanica L.). J. Hered. 93(1):52-55. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/93.1.52.

Capitani, M. I.; Spotorno, V.; Nolasco, S. M. and Tomás, M. C. 2012. Physicochemical and functional characterization of by-products from chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds of Argentina. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 45(1):94-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011. 07.012.

Cong, B.; Liu, J. and Tanksley, S. 2002. Natural alleles at a tomato fruit size quantitative trait locus differ by heterochronic regulatory mutations. Proceedings of the national academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99(21):13606-11. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 172520999.

De-Souza, F. C.; De-Sousa, F.; Espirito, G.; Da-Silva, S. and Rosa, G. 2015. Effect of chia seed (Salvia hispanica L.) consumption on cardiovascular risk factors in humans: a systematic review. Nutrición Hospitalaria. 32(5):1909-1918. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2015. 32.5.9394 retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85622739007%0ACómo.

Fernald, M. L. 1907. Diagnoses of new spermatophytes from Mexico. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. https://doi.org/ http://www.jstor.org/stable/20022302. 43(2):(61-68).

Harlan, J. R. 1992. Grass evolution and domestication. In C. U. Press. (Ed.). Origins and processes of domestication. In: Chapma, G. P (Ed.). Cambridge University Press. 156-175 pp.

Hernández, G. A. y Miranda, C. S. 2008. Caracterización morfológica de chía (Salvia hispanica). Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 31(2):105-113. https://doi.org/0187-7380.

Loreto, M. A.; Cobos, A.; Diaz, O. and Aguilera, J. M. 2013. Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica L.): an ancient grain and a new functional food. Food Reviews Inter. 29(4):394-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2013.818014.

Mao, L.; Begum, D.; Chuang, H. W.; Budiman, M. A.; Szymkowiak, E. J.; Irish, E. E. and Wing, R. A. 2000. JOINTLESS is a MADS-box gene controlling tomato flower abscission zone development. Nature. 406(6798):910-913. https://doi.org/10.1038/35022611.

Medina-Santos, L.C.; Covarrubias-Prieto, J.; Iturriaga, G.; Ramírez-Pimentel, J. G. y Raya-Pérez, J. C. 2019. Caracterización de colectas de chía de la región occidental de México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 10(8):1837-1848.

Oliveros, S. M. R. and Paredes, L. O. 2013. Isolation and characterization of proteins from chia seeds (Salvia hispanica L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 61(1):193-201. https://doi.org/10.1021/ jf3034978.

Olivos-Lugo, B. L, Valdivia-López, M. Á. and Tecante, A. 2010. Thermal and physicochemical properties and nutritional value of the protein fraction of Mexican chia seed (Salvia hispanica L.). Food Sci. Technol. Inter. 16(1):89-96. https://doi.org/10.1177/10820 13209353087.

Rovati, A.; Escobar, E. y Prado, C. 2009. Metodología alternativa para evaluar la calidad de la semilla de chía (Salvia hispanica L.) en Tucumán, R. Argentina. EEAOC-Avance agroindustrial. 33(3):44-46.

Sosa, B. A.; Ruiz, I. G.; Miranda, C.; Gordillo, S.; Westh, H. and Mendoza, G. 2016 b. Agronomic and physiological parameters related to seed yield of white chia (Salvia hispanica L.). Acta Fitogenética. Sociedad Mexicana de Fitogénetica, AC. 3(1):31-37.

Ullah, R.; Nadeem, M. and Imran, M. 2017. Omega-3 fatty acids and oxidative stability of ice cream supplemented with olein fraction of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) oil. Lipids in health and disease, 16(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0420-y.

XLSTAT. 2017. XLSTAT Software. Version. 5.02. Copyright addinsoft 1995-2017. http://www.xlstat.com. 2017.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.