Cold damage to fruits of mango variety Ataulfo

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v16i4.3069Keywords:

ripening degree, temperature, shipping timeAbstract

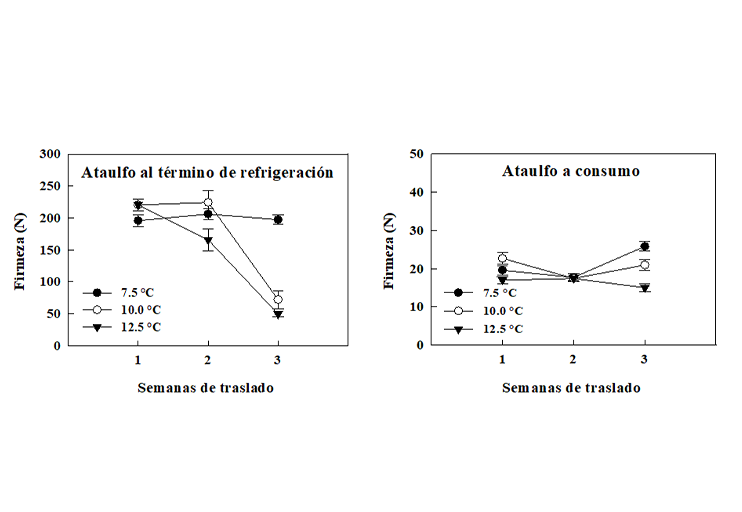

Mangoes are one of the favorite fruits in the United States market, with annual imports of 120 million boxes. One of the challenges in delivering quality fruit is that shipping from countries of origin requires up to four weeks of transport, which causes overripeness and complications for distribution to wholesalers and retailers. Shipments are made in refrigerated sea containers, which slows down the ripening process. Nonetheless, mango fruits are susceptible to cold damage when stored at low temperatures. For all these reasons, the research aimed to quantify the effect of the degree of ripeness, temperature, and transport time on cold damage in Ataulfo mango fruits. The degree of ripeness (partially ripe and ripe), storage temperatures (7.5, 10 and 12.5 °C), and refrigerated transport (1, 2 or 3 weeks) were examined. The variables evaluated were external and internal damage, pulp firmness and color, and total soluble solids. It was found that the state of ripeness had no influence on the external and internal damage of the fruits. However, the temperature affected it significantly, the lower the temperature the greater the damage. Storage time significantly influenced external damage, pulp firmness and color, and total soluble solids. The longer the storage time, the greater the damage. In addition, it was observed that the combination of temperature and storage time was significant. The damage manifested itself from the first week of transport at 7.5 °C.

Downloads

References

AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 1984. Official Methods of Analysis. 14th Ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists Inc. Arlington, VA. USA. 1006 p.

Brecht, J. K.; Nuñes, M. C. N. and Maul, F. F. 2012. Time-temperature combinations that induce chilling injury of mangos. Final report. National Mango Board. 21 p.

Brecht, J. K.; Sargent, S. A.; Kader, A. A.; Mitcham, E. J.; Maul, F. F.; Brecht, P. E. and Menocal, O. A. 2017. Mango postharvest best management practices manual. National Mango Board. 73 p.

Chaplin, G. R.; Cole, S. P.; Landrigan, M.; Nuevo, P. A.; Lam, P. F. and Graham, D. 1991. Chilling injury and storage of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit held under low temperatures. Acta Hort. (ISHS). 291(1):461-471.

Chongchatuporn, U.; Ketsa, S.; and Van-Doorn, W.G. 2013. Chilling injury in mango (Mangifera indica): relationship with ascorbic acid concentrations and antioxidant enzyme activities. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 86:409-417.

Dea, S.; Brecht, J. F.; Nunes, M. C. N.; Baldwin, E. A. 2010. Occurrence of chilling injury in fresh-cut ‘Kent’ mangoes. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 57(1):61-71.

Kader, A. A. 1992. Postharvest biology and technology: an overview. In: Kader, A. A. (Ed.). Postharvest technology of horticultural. University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. 39-48 pp.

Kader, A. A. 1997. Recommendations for maintaining mango postharvest quality. Perishables handling. https://postharvest.ucdavis.produce-fact-sheets/mango.

Lobo, M. G. and Sidhu, J. S. 2017. Biology, postharvest physiology and biochemistry of mango. In: handbook of mango fruit: production, postharvest science, processing technology and nutrition. 37-59 pp.

Luna, E. G.; Arévalo, G. M. L.; Anaya, R. S.; Villegas, M. A.; Acosta, R. M. y Leyva, R. G. 2006. Calidad del mango ‘Ataúlfo’ sometido a tratamiento hidrotérmico. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana. 29(2):123-128.

Miguel, A. C. A.; Durigan, J. F.; Morgado, C. M. A. and Gomes, R. F. O. 2011. Injúria pelo frio na qualidade pós-colheita de mangas cv. Palmer. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. 33(1):255-260.

Miguel, A. C. A.; Durigan, J. F.; Barbosa, J. C. y Morgado, C. M. A. 2013. Qualidade de mangas cv Palmer após armazenamento sob baixas temperaturas. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. 35(2):255-260.

Medlicott, A. P.; Sigrist, J. M. M. and Sy, O. 1990. Ripening of mangoes following low temperature storage. Journal of the American society for horticultural science. 115(3):430-434.

Mohammed, M. and Brecht, J. K. 2002. Reduction of chilling injury in ‘Tommy Atkins’ mangoes during ripening. Scientia Horticulturae. 95(4):297-308.

Osuna-García, J. A.; Nolasco-González, Y.; Gómez-Jaimes, R. y Pérez-Barraza, M. H. 2019. Temperaturas de refrigeración para el envío de mango ‘Kent’ y ‘Keitt hacia mercados distantes. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología Postcosecha. 20(1):26-35.

Phakawatmongkol, W.; Ketsa, S. and Van-Doorn, W. G. 2004. Variation in fruit chilling injury among mango cultivars. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 32(1):115-118.

SAGARPA, 2020. Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Vigilancia epidemiológica de moscas exóticas de la fruta. Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASICA). https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/402359/NAYARIT.pdf.

SAS-STAT. 2002. SAS Institute. User’s Guide. Version 9. SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC. 1733-1906 pp.

Sevillano, L.; Sánchez-Ballesta, M. T.; Romojaro, F. and Flores, F. B. 2009. Physiological, hormonal and molecular mechanisms regulating chilling injury in horticultural species. Postharvest technologies applied to reduce its impact. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 89(4):555-573.

USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 2020. Three years trends for US mango imports. http://www.fas.usda.gov.

Vega-Álvarez, M.; Salazar-Salas, N. Y.; López-Angulo, G.; Pineda-Hidalgo, K. V.; López-López, M. E.; Vega-García, M. O.; Delgado-Vargas, F. and López-Valenzuela, J. A. 2020. Metabolomic changes in mango fruit peel associated with chilling injury tolerance induced by quarantine hot water treatment. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 169:111299.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas accept the following conditions:

In accordance with copyright laws, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas recognizes and respects the authors’ moral right and ownership of property rights which will be transferred to the journal for dissemination in open access. Invariably, all the authors have to sign a letter of transfer of property rights and of originality of the article to Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) [National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research]. The author(s) must pay a fee for the reception of articles before proceeding to editorial review.

All the texts published by Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas —with no exception— are distributed under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows third parties to use the publication as long as the work’s authorship and its first publication in this journal are mentioned.

The author(s) can enter into independent and additional contractual agreements for the nonexclusive distribution of the version of the article published in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (for example include it into an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as it is clearly and explicitly indicated that the work was published for the first time in Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas.

For all the above, the authors shall send the Letter-transfer of Property Rights for the first publication duly filled in and signed by the author(s). This form must be sent as a PDF file to: revista_atm@yahoo.com.mx; cienciasagricola@inifap.gob.mx; remexca2017@gmail.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.